Quentin SommervilleBBC News, reporting from Bilozerske in eastern Ukraine

The white armoured police van speeds into the eastern Ukrainian town of Bilozerske, a steel cage mounted across its body to protect it from Russian drones.

They’d already lost one van, a direct hit from a drone to the front of the vehicle; the cage, and powerful rooftop drone jamming equipment, offer extra protection. But still, it’s dangerous being here: the police, known as the White Angels, want to spend as little time in Bilozerske as possible.

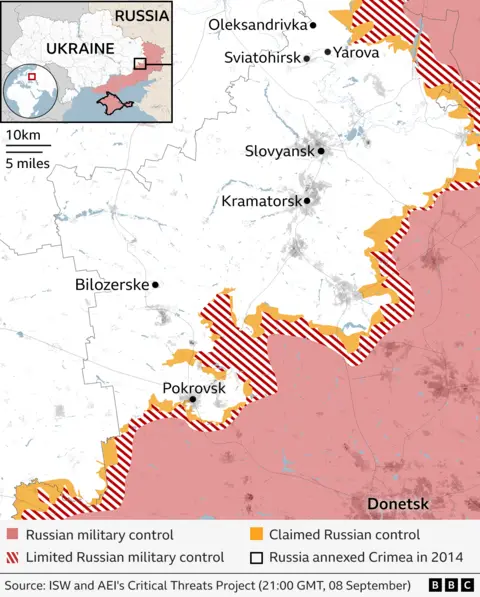

The small, pretty mining town, just nine miles (14km) from the front line, is slowly being destroyed by Russia’s summer offensive. The local hospital and banks have long since closed. The stucco buildings in the town square are shattered from drone attacks, the trees along its avenues are broken and splintered. Neat rows of cottages with corrugated roofs and well-tended gardens stream past the car windows. Some are untouched, others burned-out shells.

A rough estimate is that 700 inhabitants remain in Bilozerske from a pre-war population of 16,000. But there is little evidence of them – the town already looks abandoned.

An estimated 218,000 people need evacuation from the Donetsk region, in eastern Ukraine, including 16,500 children. The area, which is crucial to the country’s defence, is bearing the brunt of Russia’s invasion, including daily attacks from drones and missiles. Some are unable to leave, others unwilling. Authorities will help evacuate those in front-line areas, but they can’t rehouse them once they’re out of danger. And despite the growing threat from Russian drones there are those who would rather take their chances than leave their homes.

The police are looking for the house of one woman who does want to leave. Their van can’t make it down one of the roads. So, on foot, a policeman goes searching, the hum of the drone jammer and its invisible protection receding as he heads down a lane.

Eventually he finds the woman under the eaves of her cottage, a sign on her door reading “People Live Here”. She has dozens of bags and two dogs. It’s too much for the police to carry: they already have evacuees and their belongings crammed inside the white van.

The woman faces a choice – leave behind her belongings, or stay. She decides to wait. There will be another evacuation team here soon and they will take her belongings too.

To stay or go is a life-or-death calculation. Civilian casualties in Ukraine reached a three-year high in July of this year, according to the latest available figures from the United Nations, with 1,674 people killed or injured. Most occur in front-line towns. The same month saw the highest number killed and injured by short-range drones since the start of the full-scale invasion, the UN said.

The nature of the threat to civilians in war has changed. Where once artillery and rocket strikes were the main threat, now they face being chased down by Russian first person view (FPV) drones, that follow and then strike.

As the police leave town, an old man pushing a bicycle appears. He’s the only soul I see on the streets that day.

Most of those remaining in front-line towns are older people, who make up a disproportionate number of civilian casualties, according to the UN.

He tells me to move to the side of the road, out of the way of non-existent traffic. Volodymyr Romaniuk is 73 years old and is risking his life for the two cooking pots he’s collected on the back of his bike. His sister-in-law’s house was destroyed in a Russian attack, so he came today to salvage the pots.

Isn’t he afraid of the drones, I ask. “What will be, will be. You know, at 73 years old, I’m not afraid anymore. I’ve already lived my life,” he says.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCHe’s in no rush to get off the streets. A former football referee, he slowly removes a folded card from his jacket pocket and shows me his official Collegium of Football Referees card. It’s dated April 1986 – the month of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

He’s from the west of Ukraine and could return there out of harm’s way. “I stayed here for my wife,” he tells me. She’s had multiple surgeries and wouldn’t be able to make the journey. And with that, he leaves, and heads home to care for his wife, the two metal pots on the back of his bike rattling as he moves along the empty street.

Slovyansk is further back from the front, 25km away, and faces a different drone threat. Shahed drones have been dubbed “flying mopeds” by Ukrainians because of their puttering engines. Swarms of them attack Slovyansk often. There is a change in the drone’s hum before it dives and then explodes.

At night, Nadiia and Oleh Moroz hear them but still they won’t leave Slovyansk. They have poured blood and sweat into this land – and at their son’s graveside, tears too.

Serhii was 29, a lieutenant in the army killed by a cluster bomb near Svatove in November 2022. He and his father, Oleh, first fought together in 2015 against the Russians in Donbas. They worked side by side, as sappers.

Serhii’s trident-shaped grave sits on a hillside overlooking Slovyansk, his portrait and a map of Ukraine on the polished black stone.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCNadiia, 53, visits often. On the afternoon I meet her, Russian artillery is landing on a nearby hillside. But she pays little attention as she fusses around the grave and whispers sweet nothings to her dead son.

“How can you lose the place where you were born, where you grew up, where your child grew up, where he found his final rest?” she tells me through tears. “And then to live your whole life with the feeling that you will never again visit this place – I cannot even imagine that right now.”

But her husband Oleh, 55, admits they will have to leave when the fighting comes closer. “I won’t stay here, the Russians would put a target on me straight away,” he says. Until then they will stay under the nightly terror of drones so that they can remain close to their son’s final resting place.

Life’s challenges don’t stop when war arrives. All Olha Zaiets wants is time to recover from her cancer surgery. Instead, the 53-year-old and her husband Oleksander Ponomarenko, 59, had to flee their home in Oleksandrivka. The Russians were only 7.5km away and the shelling became intense. Their postwoman was killed in a Russian bombardment, and the school principal too.

“There was a strike – a missile hit the neighbouring house. And the blast wave smashed our roof tiles, blew out the doors, the windows, the gates, the fence. We had just left, and two days later it hit. If we had been there, we would have died,” she explains.

Darren Conway/BBC

Darren Conway/BBCNow they are living, temporarily, in a borrowed house in Sviatohirsk. It isn’t much better. We can hear shelling outside, the front line edges closer every day. But it will have to do. They have nowhere else to go.

“Yes, we will have to move farther away somewhere, but we don’t know how or where,” she says in a room crowded with their belongings, still waiting to be unpacked. Their life savings have gone on her hospital bills and now they are out of options.

On Tuesday they left the town to collect Olha’s test results. The news was good and she won’t have to undergo chemotherapy. “We were happy, we felt like we were flying on wings,” she said.

But while they were gone, Russia bombed the nearby town of Yarova, 4km away. It was just before 11am and older people had left their homes and gathered to collect their pensions. Some 24 were killed and 19 wounded in one of the deadliest strikes on civilians in the war so far.

On Telegram, the head of the Donetsk administration, Vadym Filashkin, decried the attack. “This is not warfare – this is pure terrorism.”

“I urge everyone,” he said, “take care of yourselves. Evacuate to safer regions of Ukraine!”

Additional reporting by Liubov Sholudko