Australia will gain access to Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) military facilities and troops under a key deal that will see the nations come to each other’s aid if either is attacked.

Both governments say the deal was born from a yearslong alliance between the two Pacific neighbours, but experts say it is aimed at countering China’s growing influence in the region.

The deal ensures China will not have the same access to infrastructure in PNG as it does in other Pacific Islands, said Oliver Nobetau, project director of the Lowy Institute’s Australia-PNG network.

It will allow as many as 10,000 Papua New Guineans to serve in Australia’s military, and give them the option to become Australian citizens.

With nearly 12 million people, PNG is the largest and most populous South Pacific nation.

China has already significantly shored up trade with Pacific Island nations in recent years, and is now trying to establish diplomatic and security beachheads across the region.

Australia and its Western allies, including the United States, have been attempting to counter these efforts.

In 2022, Beijing signed a security deal with the Solomon Islands which has seen Chinese police officers embedded across the country, with another policing agreement forged in 2023.

In response, Canberra last December struck a deal to invest A$190m ($126m; £93m) into the Solomon Islands police force and set up a police training centre, with a similar agreement in place with Tuvalu.

In August, Australia also signed a $328m security and business deal with Vanuatu, which involves the building of two data centres, strengthening of security and help dealing with the impacts of climate change.

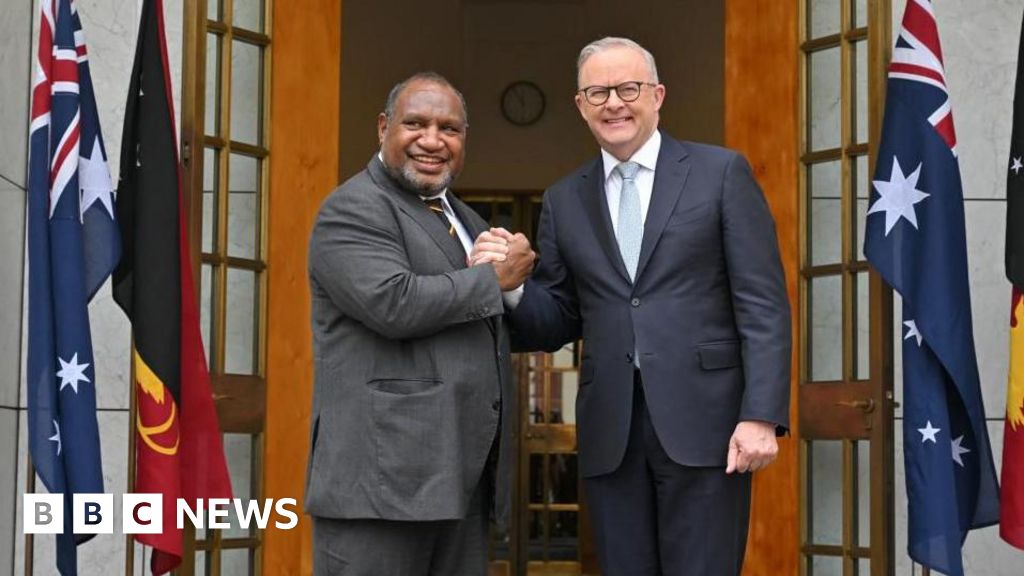

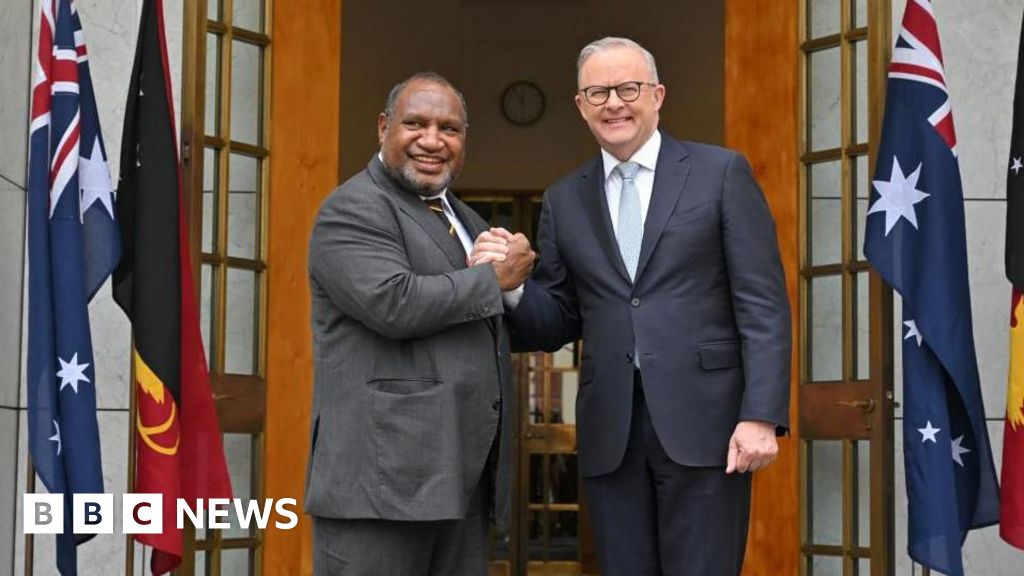

PNG Prime Minister James Marape, who signed this latest agreement with his Australian counterpart Anthony Albanese on Monday, stressed the deal was not born out of geopolitics.

PNG has been “transparent” with China, Marape said while in Canberra.

“We have told them that Australia is our security partner of choice and they understand our alliances here… Other aspects of our relations have never been compromised,” he said.

Albanese said the two countries’ alliance is “built on generations of mutual trust, and demonstrates our commitment to ensuring the Pacific remains peaceful, stable and prosperous”.

“By continuing to build our security relationships in the region, we safeguard our own security,” he said.

The Pukpuk Treaty, named after the word for “crocodile” in PNG pidgin, notes that an armed attack on either country would be “dangerous to the other’s peace and security”, so both should “act to meet the common danger”.

“[The treaty] has the ability to bite and like a crocodile, its bite force speaks of the interoperability’s and preparedness of the military for war,” according to a copy of the deal seen by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

The deal also covered greater collaboration around cyberspace and electromagnetic warfare, the documents said.

Earlier, the PNG Defence Minister Billy Joseph had told the ABC that the deal would mean Australian and PNG forces would be “totally integrated”.

Mr Nobetau from the Lowy Institute said the agreement will also help address Australia’s recent struggles recruiting for its military.

“PNG has an oversupply of able-bodied citizens who are willing to do this kind of work,” he said, adding many people would be attracted by the prospects of living in Australia and possibly gaining citizenship.

It also sends a message to the US, Mr Nobetau said.

“The US has been questionable in recent times with its withdrawal from the Pacific and USAID,” he said, referring to the Trump administration removing billions in foreign humanitarian aid.

“This is just a demonstration that PNG and Australia are capable as equal partners for managing and bringing a return to regional stability in the Pacific.”

The deal also includes annual joint military exercises which are about “strategic messaging”, Mr Nobetau said, to “show the interoperability of the forces and their ability to face an external threat in the region and how quickly they can organise themselves and deploy”.

Anna Powles, associate professor in security studies at Massey University in New Zealand, said the deal would help modernise PNG’s army, bringing a significant boost in both material and morale terms.

There were questions over how it fits with the country’s own policies though, she added.

“There are concerns in PNG that the treaty undermines PNG’s ‘friends to all, enemies to none’ foreign policy position by aligning PNG with Australia on all security matters,” she explained.

Ms Powles noted that the deal forms part of Australia’s so-called ‘hub and spokes’ network of security agreements in the Pacific – with Australia as the central hub and the island nations as the spokes – but said both sides need greater clarity on the expectations, obligations and commitments.

The deal has faced some criticism within PNG, with the country’s former defence force commander warning that it may come at “a high cost” for the country.

“It’s common knowledge that Australia sees China as a potential threat, but China is not PNG’s enemy,” the commander, Jerry Singirok, told the ABC last month.