BBC News, White House

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWarheads raining down from beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. Faster-than-sound cruise missiles striking US infrastructure. Sky-high nuclear blasts.

These are just some of the nightmarish scenarios that experts warn could come true if the US’s dated and limited defence systems were overwhelmed in a future high-tech attack.

Even a single, relatively small nuclear detonation hundreds of miles above the heads of Americans would create an electromagnetic pulse – or EMP – that would have apocalyptic results. Planes would fall out of the sky across the country. Everything from handheld electronics and medical devices to water systems would be rendered completely useless.

“We wouldn’t be going back 100 years,” said William Fortschen, an author and weapons researcher at Montreat College in North Carolina. “We’d lose it all, and we don’t know how to rebuild it. It would be the equivalent of us going back 1,000 years and having to start from scratch.”

In response to these hypothetical – but experts say quite possible – threats, US President Donald Trump has set his eyes on a “next generation” missile shield: the Golden Dome.

But while many experts agree that building such a system is necessary, its high cost and logistical complexity will make Trump’s mission to bolster America’s missile defences extremely challenging.

An executive order calling for the creation of what was initially termed the “Iron Dome for America” noted that the threat of next-generation weapons has “become more intense and complex” over time, a potentially “catastrophic” scenario for the US.

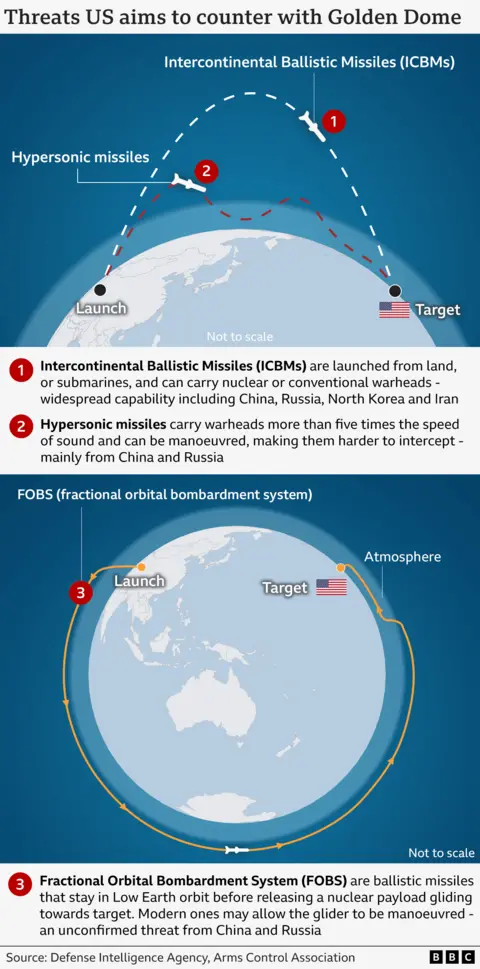

Patrycja Bazylczyk, a missile defence expert at the Washington DC-headquartered Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the BBC that existing systems are geared towards intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, such as those used by North Korea. But powerful nations like Russia and China are also investing in newer technologies that could strike not just neighbours, but adversaries an ocean away.

Among the threats publicly identified by US defence officials are hypersonic weapons able to move faster than the speed of sound and fractional orbital bombardment systems – also called Fobs – that could deliver warheads from space.

Each – even in limited numbers – are deadly.

“The Golden Dome sort of re-orients our missile defence policy towards our great power competitors,” Ms Bazylczyk said. “Our adversaries are investing in long-range strike capabilities, including things that aren’t your typical missiles that we’ve been dealing with for years.”

What will the ‘Golden Dome’ look like?

The White House and defence officials have so far provided few concrete details about what the Golden Dome – which is still in its conceptual stages – would actually look like.

Speaking alongside Trump in the Oval Office on 20 May, defence secretary Pete Hegseth said only that the system will have multiple layers “across the land, sea and space, including space-based sensors and interceptors”.

Trump added that the system will be capable of intercepting missiles “even if they are launched from other sides of the world, and even if they are launched in space”, with various aspects of the programme based as far afield as Florida, Indiana and Alaska.

In previous testimony in Congress, the newly named overseer of the programme, Space Force General Michael Guetlein, said that the Golden Dome will build on existing systems that are largely aimed at traditional ICBMs. A new system would – add multiple layers that could also detect and defend against cruise missiles and other threats, including by intercepting them before they launch or at the various stages of their flight.

Currently, the US Missile Defence Agency largely relies on 44 ground-based interceptors based in Alaska and California, designed to combat a limited missile attack.

Experts have warned that the existing system is woefully inadequate if the US homeland were to be attacked by Russia and China, each of which has an expanded arsenal of hundreds of ICBMs and thousands of cruise missiles.

“[Current systems] were created for North Korea,” said Dr Stacie Pettyjohn, a defence expert at the Center for a New American Security. “It could never intercept a big arsenal like Russia’s, or even a much smaller one like China’s.”

The Congressional Research Office, or CBO, has said that “hundreds or thousands” of space-based platforms would be necessary to “provide even a minimal defence” against incoming missiles – a potentially enormously expensive proposition.

Israel’s Iron Dome: an example?

Trump first revealed his concept for the Golden Dome during a joint address to Congress in March, when he said that “Israel has it, other places have it, and the United States should have it too”.

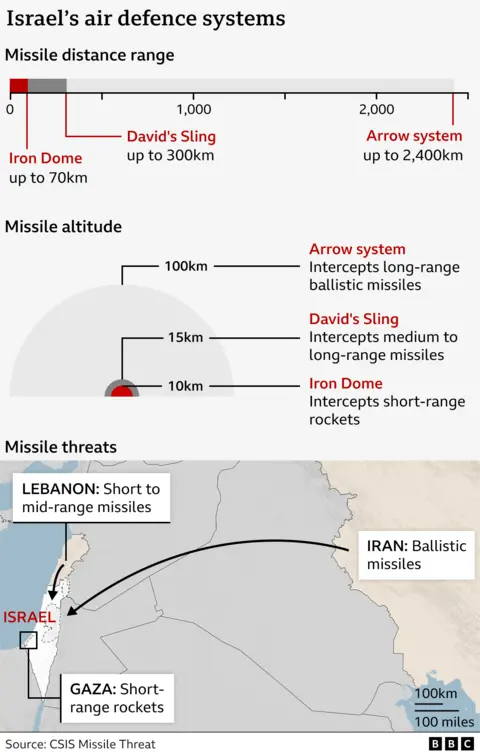

The president was referring to Israel’s “Iron Dome” system, which the country has used to intercept rockets and missiles since 2011.

Israel’s Iron Dome, however, is designed to intercept shorter-range threats, while two other systems – known as David’s Sling and the Arrow – combat larger ballistic missiles such as those that have been fired by Iran and the Houthis in Yemen.

Ms Bazylczyk described the Iron Dome as geared towards “lower tier” threats, such as rockets fired from Gaza or southern Lebanon.

The Golden Dome would go beyond that, to detect longer range missiles as well, she said.

To accomplish that, she said it will need to combine different capabilities.

“And I’ll be looking out for the command and control system that can weave all of this together,” she said, noting that such a thing does not currently exist.

Can it be done?

Creating that system will be an incredibly complicated – and costly – proposition.

In the Oval Office, Trump suggested that the Golden Dome could be completed by the end of his term, with a total cost of $175bn over time, including an initial investment of $25bn already earmarked for it.

His estimate is far out of sync with the CBO’s, which has put the potential price tag at $542bn over 20 years on the space-based systems alone. Experts have said the total cost could eventually soak up a large chunk of the massive US defence budget.

“I think that’s unrealistic,” said Dr Pettyjohn. “This is complicated, with multiple systems that need to be integrated together. Every one of those steps has its own risks, costs and schedules.”

“And going fast is going to add more cost and risk,” she added. “You’re likely to produce something that isn’t going to be as thoroughly evaluated… there are going to be failures along the way, and what you produce may need major overhauls.”

The creation of the Golden Dome has also sparked fears that it may lead to a new “arms race”, with US foes gearing up their own efforts to find ways to overwhelm or circumvent its defences.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning, for example, told reporters that the plan “heightens the risk of space becoming a battlefield”.

Those involved in researching worst-case scenarios and US defence policy downplay these concerns. Potential foes, they argue, are already investing heavily in offensive capabilities.

“The Golden Dome aims to change the strategic calculus of our adversaries,” said Ms Bazylczyk. “Improving homeland air and missile defences reduces the confidence of a potential attacker in achieving whatever objectives they seek.”

“It raises the threshold for them to engage in this attack,” she added. “And it contributes to overall deterrence.”

Even a partially completed Golden Dome, Mr Fortschen said, could prevent a nightmare scenario from taking place.

“I will breathe a lot easier,” he said. “We need that type of system. The Golden Dome is the answer.”