Bob HowardDublin

NurPhoto via Getty Images

NurPhoto via Getty ImagesJack likes a drink and a standard night out will probably involve several pints at his local.

“If you have three pints, that is easy, easy going,” the 29-year-old says. “Probably a heavy night, casually, would be like six-plus pints.”

Jack grew up in County Galway where, he says, young people often start drinking at 14 or 15, “usually in a field with a horrendous can of cider”.

“And then, when you’re 17, your dad brings you to a pub, buys you your pint of Guinness, and that’s where it takes hold.”

Ireland has a complex relationship with drinking and many see alcohol and socialising as inextricably linked, part of the social fabric of everyday life.

Pubs tend to be the focal point of communities where there’s often live music, and many traditional songs celebrate or speak of the harms of having one too many. Huge brands such as Guinness and Jamesons are major exports.

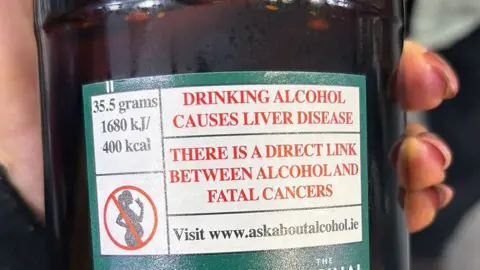

Since 2020 supermarkets and corner shops across the country have had to erect physical barriers between sections selling alcoholic drinks and general products, while some bottles and cans of alcohol now carry among the strongest warning labels anywhere in the world.

First signed into Irish law in 2023, products with the new labels – which state drinking causes liver disease and is linked to fatal cancers – are already on sale in pubs and supermarkets across the country.

But in a move condemned by public health advocates, the Irish government has delayed their compulsory introduction until 2028, blaming uncertainty with world trade – which some believe is the result of lobbying by the drinks industry.

For its part, the industry body, Drinks Ireland, said it did look to the Irish government to give some “breathing space” on health warning labels and that it believes they should be agreed on an EU-wide level.

It was when Jack moved to Dublin in 2015 to study journalism that he really got to know the capital’s nightlife.

“Dublin’s a great spot because it’s always spontaneous drinking, and that’s why it’s famous,” he says. “It’s very pub-centric, drink-heavy.”

A big weekend night out for Jack usually begins with pre-drinks at someone’s house – perhaps a bottle of gin mixed with tonic shared between him and three friends – before going on to a club for shots.

Yet even though he sometimes drinks a considerable amount, Jack, who works in advertising, says he knows his limits and feels healthy.

“I’m a pretty fit person, I ran a marathon a year ago,” he says. “I know my limits. As long as you know what your limits are, I think its fine, health-wise.”

Three-quarters of the population here drink and celebrations, from birthdays to weddings, often involve alcohol.

Consumption has fallen by around a third over the past 25 years, according to figures from The Drinks Industry Group of Ireland (DIGI).

Young people, on average, now start drinking at 17 – two years older than the average 20 years ago. But once they start, their consumption and binge drinking is among the highest in Europe.

A report from public health advocacy group Alcohol Action Ireland found the proportion of 15-24-year-olds consuming alcohol had risen – from 66% in 2018, to 75% in 2024 – and that two out of three 15-24-year-olds regularly binge-drink.

Campaigners believe Ireland’s alcohol warning labels are making an incremental impact. But 23-year-old Amanda, who’s seen the labels, isn’t so sure.

“You look at it and you’re like, ‘Oh, I just drank that. Should I drink another one?'”

Amanda doesn’t think people will pay much attention to the health warnings and reckons they might even make some more inclined to drink.

“I just don’t think they care,” she says.

On a night out in Dublin Amanda says she will usually limit herself to a maximum of three drinks.

“I like to be in control of what I do when I’m out,” she says. “I don’t really drink that much for letting loose.”

She’s mindful of how young people are perceived on social media, and that influences her own drinking choices.

“I don’t like taking photos with myself with a glass of wine or Guinness,” she says. “You don’t want to be in compromising positions, you don’t want people to have a negative image.”

Twenty-one-year-old Sean lives in the capital and likes to socialise with friends – some are drinkers, while others are not.

Unlike in other parts of Europe, Sean says if you want to socialise in the evenings there aren’t many options here, other than going to the pub.

“There’s not much to do in Dublin after a certain time,” Sean says. “Six to seven or so the city kind of shuts down. At times you’d just be like, ‘I’m really not in the humour to have a pint, but I want to sit somewhere and see my friends’ – so you have to get a pint.”

He’s seen the alcohol warning labels too, but isn’t sure they will put him off drinking.

“Everyone kinda knows it’s bad for you, but we do it anyway,” he says.

Cigarette warning labels are “far more graphic”, Sean’s friend Mark adds.

Ireland was the front-runner in restricting smoking and since 2004 you can’t smoke in the workplace or restaurants and bars.

Even before the introduction of the new warning labels, some young Irish people in their 20s have been finding they are better off without alcohol in their lives.

Mark rarely drinks. It’s “one for my birthday, one for Christmas”, he says, in part because alcohol is expensive and it’s cheaper to opt for something else.

“I don’t really like the taste of it,” the 21-year-old says. “Guinness is probably the one I would have, but also the cost of it – I am saving so much money by just getting the Club Orange.”

Helen is 27 and when she was younger used to drink regularly. Although she hasn’t given up alcohol completely, like Mark she says she can largely live without it.

“The last time I had a drink was February,” Helen says. “It just kind of dwindled off to this point where I’m more or less sober, but I just don’t identify as that because I may have a drink again – or maybe I won’t.”

Helen’s friend Sam – who started drinking when he was “16 or 17” – has gone a step further.

“It was a bit of fun then [I] went to college and the drinking kind of took off,” Sam, who’s now 27, says. “One day I just kind of realised it was going too far. My dad said to me, ‘What are you doing with your life? You really need to pack it in.'”

In 2021 Sam signed up to a year-long no-beer course and then quit alcohol completely. He’s not had a drink now in three years and has even given up playing the concertina in pubs because it was so ingrained to have a drink at a session. When he does go to a pub he’ll opt for a zero-alcohol drink.

But he says it sometimes seems difficult for people to accept he’s teetotal.

“There’s the odd person that you meet and you tell them you’re not drinking and they kind of look at you sideways.”

Unlike Sam, Jack’s not keen on zero-alcohol drinks, and thinks they’re “a waste of time, because it’s the same price as a pint”.

He’s thought about giving up drinking, but his inner resolve never lasts long.

“Honestly, it’s quite difficult to try and embark on the sober journey in Ireland – because it is intrinsically entwined into our culture,” Jack says.

“I always kind of flirt with the idea of going totally sober – but then I instantly dissuade [myself] and have a pint.”

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesThe BBC asked the Irish government why it had postponed the compulsory introduction of the new alcohol warning labels until 2028. It said the decision to defer was made following concerns raised about the impact of their implementation in the current global trading environment.