Charlie Northcott and

Ben Milne

BBC

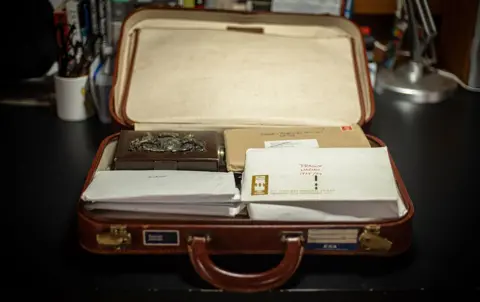

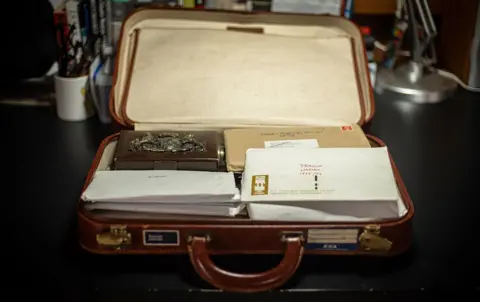

BBCIt started with a suitcase hidden under a bed.

It was 2009, and Antony Easton’s father, Peter, had recently died. As Antony started to engage with the messy business of probate, he came across a small brown leather case in his father’s old flat in the Hampshire town of Lymington.

Inside were immaculate German bank notes, photo albums, envelopes full of notes recording different chapters of his life – and a birth certificate.

Peter Roderick Easton, who had prided himself on his “Englishness” (and been an Anglican) had, in fact, been born and raised in pre-war Germany as Peter Hans Rudolf Eisner, a member of one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Berlin.

Charlie Northcott/BBC

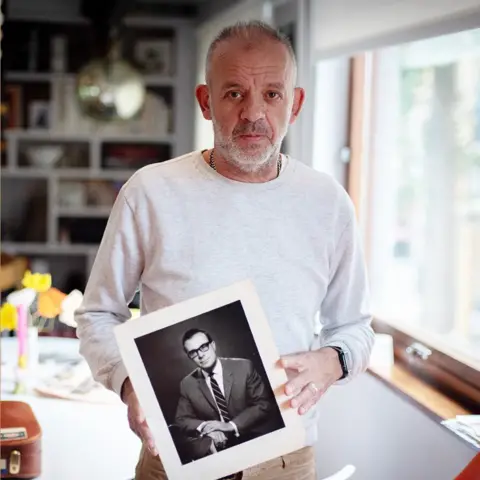

Charlie Northcott/BBCDespite hints about his father’s origins growing up, the contents of the suitcase shone a light into a past that Antony knew almost nothing about. The revelations would lead him on a decade-long trail, revealing a family devastated by the Holocaust, a vanished fortune worth billions of pounds and a legacy of artwork and property stolen under Nazi rule.

Black-and-white photographs gave a glimpse of Peter’s early life, far removed from his son’s modest upbringing in London – they showed a chauffeur-driven Mercedes, mansions staffed by servants, staircases ornately carved with angels.

More ominously, one picture showed 12-year-old Peter Eisner smiling with friends, a Nazi flag rippling in the distance.

Antony Easton

Antony Easton“I felt it was a hand reaching out from the past,” says Antony.

He says his father was a quiet and serious man, if prone to bouts of anger. He avoided talking about his childhood and always shut down questions about his slight German accent.

“There were clues that [he wasn’t] really like other people… There was a darkness around his world,” says Antony.

An immense fortune

The next big clue about Antony’s family history came from a work of art.

Enlisting the help of a friend who spoke fluent German, he asked her to dig into a company called Hahn’sche Werke, references to which were peppered among the documents in the suitcase. After searching online, she sent Antony a photo of a painting, depicting the inside of a large steelworks – seemingly owned by the business

Molten metal glows hot on a conveyor belt, illuminating the faces of busy and attentive workers. It is an image of industrial power and might, from an era when Germany was hurtling towards decades of devastating war.

The 1910 painting, by the artist Hans Baluschek, was called Eisenwalzwerk (Iron Rolling Mill). It had been owned, and was likely commissioned by Heinrich Eisner, who had helped build the Hahn’sche Werke steel business into one of the most high-tech and sprawling companies in central Europe. The documents in the suitcase showed that this was Antony’s great-grandfather.

Antony Easton

Antony EastonMore research revealed that, at the turn of the 20th Century, Heinrich was one of the wealthiest businessmen in Germany – the equivalent of a modern multi-billionaire.

His company manufactured tubular steel, with factories spread across Germany, Poland and Russia.

Heinrich, and his wife, Olga, owned several properties in and around Berlin, including an impressive six-storey property in the city centre with marble floors and a cream-white facade.

A photograph from the early 1900s shows a man with a softly rounded belly and a straight white moustache. Heinrich wears a black suit, and Olga sits next to him, crowned with a crystal tiara.

Antony Easton

Antony EastonWhen he died in 1918, Heinrich left shares in his company – and his personal fortune – to his son Rudolf, recently returned from fighting in World War One.

The war had been a human catastrophe, but Hahn’sche Werke had prospered in that period, satisfying the German military’s demand for steel. Rudolf and his family also successfully weathered the economic and political chaos which haunted their country after the fighting.

However, in a few years, all would be lost.

Everything changes

In notes found by Antony in the suitcase, Peter recalled overhearing conversations between his parents, and whispers about Nazi threats. Jews were being blamed by Adolf Hitler and his supporters for Germany’s defeat in WW1, and for the economic travails that followed.

Rudolf Eisner believed he would be safe if he made his company invaluable to the Nazi regime. For a time, this seemed to work, but as anti-Jewish laws became more and more extreme, and the abuse they witnessed around them worsened, he began to reconsider.

In March 1938, the government came after Hahn’sche Werke. Under immense pressure from the authorities, the Jewish-owned company was sold at a fire-sale price to Mannesmann, an industrial conglomerate whose CEO, Wilhelm Zangen, was a Nazi supporter.

Getty Images

Getty Images“It is almost impossible to quantify the wealth stolen and how much those assets are worth today,” says David de Jong, author of the book Nazi Billionaires, which retraces the looting of Jewish businesses under the Third Reich.

In 2000, Mannesmann was taken over by Vodafone in a deal worth more than £100bn – the largest commercial acquisition on record at the time. At least a portion of the industrial assets included in that sale would have once been part of the Eisner business empire.

The dismantling of Hahn’sche Werke, and the arrest of members of the company, made the Eisners realise they needed to flee. But by 1937, any Jewish family who tried to leave Germany was forced to surrender 92% of its wealth to the state – paying a host of levies known as the Reichsfluchtsteuer or Reich Flight Tax.

The Eisners faced losing what remained of their wealth.

The deal

At the height of this crisis, a man named Martin Hartig, an economist and tax adviser according to records in Berlin’s archives, began to loom large in the Eisners’ lives.

Throughout the 1930s, his name had featured repeatedly in the guest book at the Eisner country estate, thanking them for their generous hospitality.

Herr Hartig, who wasn’t Jewish, appears to have offered the family a solution to the impending confiscation of their assets by the Nazis. They signed over key elements of their personal fortune to him – chiefly the multiple properties they owned and their contents – thereby sheltering them from laws targeting Jews.

Antony Easton

Antony EastonAntony believes his grandparents assumed Hartig would one day give the assets back to them.

They were wrong. Instead, he permanently transferred the Eisner assets into his own name.

The BBC found copies of the original sales documents in Germany’s federal archives and shared them with three independent experts. All three concluded that this deal was evidence of a “forced sale” – a term widely used to describe the dispossession of Jewish assets under the Nazis.

Despite losing the fortune they had built over generations, Antony’s grandparents and father managed to escape Germany in 1938. Train tickets, luggage tags and hotel brochures preserved in Peter’s suitcase allowed Antony to retrace their journey.

The family went to Czechoslovakia and then Poland, barely staying one step ahead of the Nazis, before catching one of the last ships bound for England in July 1939.

Charlie Northcott/BBC

Charlie Northcott/BBCThey had lost the equivalent of billions, but they were among the luckier members of the Eisner family. Most of their relatives were rounded up and killed in concentration camps. Rudolf himself died in 1945 after having spent most of the war – like many other German refugees – interned by the British on the Isle of Man.

Meeting the Hartigs

The next step for Antony was to find out what had happened to the Eisner family fortune, and to Martin Hartig.

He hired an experienced investigator, Yana Slavova, to find out what exactly had been stolen, how it had changed hands, and where it was today.

Within weeks, Yana had uncovered troves of documents about his relatives, including details of their properties and possessions.

She was able to trace the painting Antony had discovered at the beginning of his journey. Eisenwalzwerk was in the collection of the Brohan Museum in Berlin.

Early attempts to reclaim the artwork ran into problems regarding the evidence. Could Antony prove that its sale was tied to Nazi persecution? How did he know it hadn’t changed hands multiple times legitimately before ending up in the museum?

A breakthrough came when Yana unearthed correspondence between the museum and an art dealer at the time of the sale.

The art dealer had sold the painting from one of the Eisners’ former family homes – a property taken over by Martin Hartig in 1938. Hartig had lived the rest of his life there, meticulously restoring the building after damage during the fall of Berlin, before dying of natural causes in 1965.

After Hartig’s death, the property passed to his daughter, who was now in her 80s. She had gifted the house to her own children in 2014, and had moved to a country cottage, where she arranged to meet Antony and Yana.

The elderly lady made them tea and cakes, which they ate in the living room under a portrait of her father – a man with thick-rimmed glasses and oiled hair, gaunt in the face and wearing a black suit. It had been painted in 1945, just after the end of World War Two.

Martin Hartig’s daughter had a very different story to the one Antony and Yana were expecting.

She told them her father had always been opposed to the Nazis and had helped save the Eisners, who she described as great friends, from the Holocaust. She said he helped convince them to get away, urging the family: “You can’t stay here. Go to Great Britain, to London.”

Her father had also told her he helped them smuggle paintings out of Germany by taking them out of their frames and hiding them among clothes.

When asked about the properties her family took over from the Eisners in 1938, she said they were all legitimate purchases.

“My father bought two houses, legally,” she said. “It always had to be very correct.”

Antony Easton

Antony EastonOther members of the family were more open to the possibility that their ancestor may have exploited the Eisners.

Vincent, Martin Hartig’s great-grandson, is in his 20s and training to be a carpenter.

He admitted to feeling that his home, where Antony’s grandparents once lived, may have had an uncomfortable past.

“I mean of course I was curious at some point – where does it come from that we as a family live in this nice place,” he said. “I’ve also asked myself the question, how were the circumstances?”

After discovering what happened to Antony’s Jewish family, Vincent said he thought the Eisners had little choice when they passed their property to his great-grandfather.

‘It’s not about the money’

Antony has no recourse for filing a restitution case for his grandparents’ property.

His grandmother, Hildegard – Rudolf’s widow – tried to reclaim it in the 1950s, but backed down after a legal challenge by Hartig. The statute of limitations for Jewish victims of Nazi persecution to claim properties in former West Germany has also now passed.

For the artworks taken from the Eisner family, however, there is still hope for recovering what was lost.

Earlier this year, the Brohan Museum in Berlin informed Antony that it intended to return the Eisenwalzwerk painting to the descendants of Henrich Eisner. The museum declined an interview with the BBC while the process remains ongoing.

Another painting has been returned to Antony from the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and a third claim for an artwork in Austria also remains outstanding.

Among the evidence Antony’s investigation has unearthed is a list made by the Gestapo, detailing specific artefacts and paintings which were seized from his relatives. There is a chance his family could find and reclaim more assets in the future.

“I’ve always said about restitution, it’s not about objects and money and property, it’s about people,” says Antony. In researching his family’s past, he has recovered detailed knowledge of who his father and his grandparents once were.

“All of this process has turned them into real people, who had real lives.”

Antony Easton

Antony EastonThis knowledge has now been passed on to a new generation. The Eisner name may have disappeared when Peter sailed to Britain in 1939, but it now lives again. Antony’s great-nephew, Caspian, born in August 2024, was given the middle name of Eisner.

Antony says he was deeply moved by his niece’s decision to honour their long-lost family.

“You know, as long as Caspian’s around, that name will still be around with him,” he says. “People will say, ‘that’s an interesting middle name – what’s the story there?'”