Lily Jamali,North America Technology Correspondent, San Franciscoand

Tiffanie Turnbull,Sydney

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Stephen Scheeler became Facebook’s Australia chief in the early 2010s, he was a true believer in the power of the internet, and social media, for public good.

It would herald a new era of global connection and democratise learning. It would let users build their own public squares without the traditional gatekeepers.

“There was that heady optimism phase when I first joined and I think a lot of the world shared that,” he told the BBC.

But by the time he left the firm in 2017, seeds of doubt about its work had been planted, and they’ve since bloomed.

“There’s lots of good things about these platforms, but there’s just too much bad stuff,” he surmises.

That’s no longer an uncommon view as scrutiny of the largest social media companies has increased around the globe. A lot of it has centred on teenagers, who have emerged as a lucrative market for incredibly wealthy global firms – at the expense of their mental health and wellbeing, according to critics.

Various governments, from the state of Utah to the European Union, have been experimenting with limiting children’s use of social media. But the most radical step so far is set to unfold in Australia – a ban for under-16s that has left tech companies scrambling.

Many of the social media firms affected have spent a year loudly protesting the new law, which requires them to take “reasonable steps” to keep underage users from having accounts on their platforms.

They have claimed this ban actually risks making children less safe, argued it impinges on their rights, and repeatedly pointed to the questions around the the tech that will be used to enforce the policy.

“Australia is engaged in blanket censorship that will make its youth less informed, less connected, and less equipped to navigate the spaces they will be expected to understand as adults,” said Paul Taske from NetChoice, a trade group representing several big tech companies.

The worry inside the industry is that Australia’s ban – the first of its kind – may inspire other countries.

“It could become a proof of concept that gains traction around the world,” says Nate Fast, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business.

Whistleblowers, lawsuits and questions

Getty Images

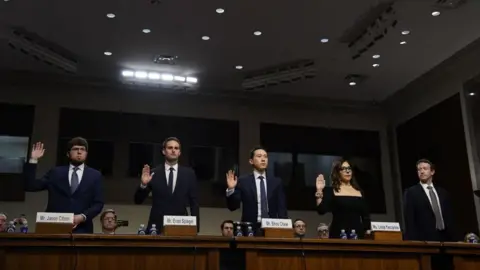

Getty ImagesIn recent years, multiple whistleblowers and lawsuits have claimed that social media firms are prioritising profits over user safety.

In January, a landmark trial will begin in the US hearing allegations that several – including Meta, TikTok, Snapchat and YouTube – have designed their apps to be addictive and knowingly covered up the harm their platforms cause. All deny this, but Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg and Snap boss Evan Spiegel have both been ordered to testify in person.

The case consolidates hundreds of claims from parents and school districts, and is among the first to advance from a flood of similar lawsuits which allege social media contributes to poor mental health and child exploitation.

In another ongoing case, state prosecutors alleged that Zuckerberg personally scuttled efforts to improve the wellbeing of teens on the company’s platforms, including vetoing a proposal to ditch Instagram face-altering beauty filters which experts say fuel body dysmorphia and eating disorders.

Former Meta employees Sarah Wynn-Williams, Frances Haugen and Arturo Béjar have given testimony before the US Congress alleging a range of wrongdoing they observed during their stints at the company.

Meta maintains the company has worked diligently to create tools that keep teens safe online.

But the broader industry has also recently been taken to task over mis- and disinformation, hate speech and violent content.

Graphic footage of the assassination of Charlie Kirk was rapidly spread on various platforms, even confronting people who were not seeking it out. Elon Musk has sued states in the US over laws that require social media firms, including X, to define and disclose how they fight hate speech online. And Meta was heavily criticised earlier this year after announcing it was getting rid of factcheckers who monitor its platforms for misinformation.

A rare bipartisan front has emerged among American lawmakers eager to cut tech bosses down to size.

During a hearing last year, Zuckerberg was prodded by one to apologise to bereaved families who had come to watch in person. Among those in the audience was Tammy Rodriguez, whose 11-year old daughter Selena took her life after facing sexual exploitation on Instagram and Snapchat.

“This is why we invest so much and we are going to continue doing industry wide efforts to make sure no one has to go through the things your families have had to suffer,” Zuckerberg said.

Public scrutiny and private lobbying

However, there’s widespread criticism from many experts, lawmakers and parents – even kids – who feel social media companies are hiding from genuine action and accountability on these issues.

As Australia’s social media ban was considered, then formulated, the firms had little to say publicly.

“Hiding from the public discourse… it just breeds more suspicion and more distrust,” Mr Scheeler says.

Privately though, many were seeking to bend the government’s ear. Spiegel personally sat down with Australia’s Communications Minister Anika Wells. She also claimed YouTube had sent globally renowned children’s entertainers The Wiggles to lobby on their behalf.

In carefully worded public statements, several of the firms have tried to push responsibility elsewhere. Meta and Snap both said operators of the major app stores – namely Apple and Google – should take on age verification duties.

And many argued government is overstepping. Parents know best, they say, and they should decide what makes sense for their teens when it comes to social media use.

“While we’re committed to meeting our legal obligations, we’ve consistently raised concerns about this law… There’s a better way: legislation that empowers parents to approve app downloads and verify age allows families – not the government – to decide which apps teens can access,” a statement from Meta provided to the BBC said.

Asked why her government was unsympathetic to this reasoning – why anything short of a ban was unacceptable – Wells said the tech companies have had plenty of time to improve their practices.

“They have had 15, 20 years in this space to do that of their own volition now, and… it’s not enough.”

Leaders in other countries feel the same, and have been knocking on her door for help, she says, rattling off the EU, Fiji, Greece, even Malta, as examples.

Denmark and Norway have already begun work on similar laws, and Singapore and Brazil are watching closely too.

“We’re pleased to be the first, we’re proud to be the first, and we stand ready to help any other jurisdiction who seeks to do these things,” Wells said.

Too little, too late?

As the Australia ban loomed, the mounting pressure prompted the companies to introduce versions of their products marketed as safer for young users, said Pinar Yildirim, a marketing professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Australia, after all, is a major market for social platforms. At parliamentary hearings in October Snapchat said it believed it had about 440,000 account users in the country aged between 13 and 15. TikTok said it had about 200,000 under-16 accounts and Meta said it had about 450,000 between Facebook and Instagram.

Experts say they are also eager to ensure they don’t lose others in even larger markets around the world.

In July, YouTube announced the rollout of AI technology that estimates a user’s age in a bid to identify those younger than 18 and better shield them from harmful content.

Snapchat has special accounts for children which it says put safety and privacy settings on by default for users between the ages of 13 and 17.

And last year, Meta unveiled Instagram Teen accounts which similarly place users younger than 18 into more restricted privacy and content settings that Meta says are designed to limit unwanted contacts and exposure to explicit content. This development was accompanied by a massive marketing blitz in the US.

“If they create a more protected environment for these users, the thinking is, that may reduce some of the damage,” Yildirim said.

Yet critics aren’t satisfied. Béjar, one of the Meta whistleblowers, led a study published in September that found almost two thirds of the new safety tools on Meta’s Instagram Teen accounts were ineffective.

“The key issue here is that Meta and other social media companies aren’t substantively addressing the harm we know teens are experiencing,” Béjar told the BBC.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesForced onto the defensive, the companies have attempted to convey that they are making a good faith effort to comply with Australia’s impending ban despite their disagreement with it.

But analysts say they’ll be hoping the hurdles – which include legal challenges, technology loopholes for kids, and any unintended consequences of the ban – could bolster the case against such moves in other nations.

And the companies “have a fair bit of influence in how smoothly things go”, Professor Fast points out.

“[They] have an incentive to walk the very fine line about complying, but making sure that they don’t comply so good that all the rest of the other countries go, ‘Great, that works. Let’s do the same’,” Mr Scheeler agrees.

Supplied

SuppliedAnd the fines – a maximum of A$49.5m ($33m, £24.5m) for serious breaches – might just be seen as the cost of doing business, according to Carnegie Mellon University marketing professor Ari Lightman. “[They’re] a drop in the bucket,” he says, especially for larger players eager to secure their next generation of potential users.

Despite the concerns around the policy’s implementation, Mr Scheeler says he feels like this is a “seatbelt moment” for social media.

“Some would argue that bad regulation is worse than no regulation, and sometimes that’s true, but I think in this instance, even imperfect regulation is better than nothing, or better than what we had before,” he says.

“Maybe it will work, maybe it won’t work, but at least we’re trying something.”