Editor, BBC Global Disinformation Unit

BBC Global Disinformation Unit

BBC

BBCJavier Gallardo likes to start his morning watching a classical music programme on television – it is part of his routine, and puts him in the right mood for the day before going to work driving trucks.

But one Monday in June, he turned on the television and, instead of music, the screen was filled with images of a warzone. A news report was playing on a channel he had never heard of.

“What’s happening?” he asked himself. After 20 minutes, he turned it off. “I couldn’t connect with it.”

A green logo at the bottom corner of the screen showed the letters: “RT”. Searching online, he found that this was a Russian channel.

Javier lives in Chile. It is alleged that Telecanal, a privately-owned TV channel in the country, has handed over its signal to Russian state-backed news broadcaster RT, formerly Russia Today.

Photo by YURI KADOBNOV/AFP via Getty Images

Photo by YURI KADOBNOV/AFP via Getty ImagesThe country’s broadcasting regulator has opened sanction proceedings against Telecanal for a possible violation of broadcasting law, and is waiting for the channel’s response.

Telecanal did not respond to request for comment.

Viewers, meanwhile, were left confused.

“I got upset,” admits Javier. “They didn’t announce anything beforehand, and I couldn’t understand why.”

Over the last three years, the Russian state-backed news channel RT and news agency and radio Sputnik, have expanded their international presence; between them, they now broadcast across Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Latin America.

This all coincides with bans in Western countries.

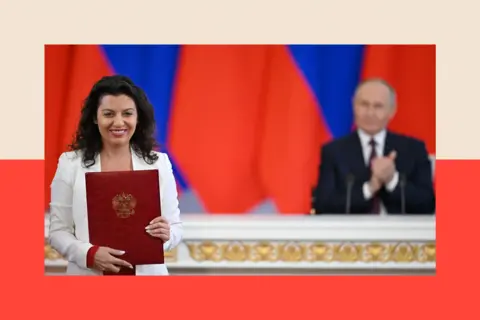

Kirill KUDRYAVTSEV / AFP

Kirill KUDRYAVTSEV / AFPFollowing Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, sweeping restrictions were imposed to RT’s broadcasting in the US, UK, Canada and across the European Union – as well as by major tech companies – for spreading disinformation about the war.

This culminated in 2024, when US authorities sanctioned RT executives – including its editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan – for alleged attempts to harm “public trust” in the country’s institutions.

It came amid accusations of the Kremlin orchestrating a widespread campaign to interfere in the presidential election. RT denied involvement.

Yet elsewhere, RT’s influence has only expanded.

Since 2023, RT has opened a bureau in Algeria, launched a TV service in Serbian, and started free training programmes aimed at journalists from Africa, Southeast Asia, India, and China.

The broadcaster has also announced it will open an office in India. Sputnik, meanwhile, launched a newsroom in Ethiopia in February.

All of this coincides with an apparent weakening from the Western media in some regions. Thanks to budget cuts and changing foreign policy priorities, certain outlets have downsized and even withdrawn from parts of the world.

Two years ago, the BBC closed its Arabic radio service in favour of its digital-based service – which provides audio, video and text-based news content. It has since launched emergency radio services for Gaza and Sudan. That same year Russia’s Sputnik started a 24-hour service in Lebanon, occupying the airwave vacated by BBC Arabic.

Meanwhile, the US government-funded international broadcasting service Voice of America has cut most of its staff.

“Russia is like water: where there are cracks in the cement, it trickles in,” says Dr Kathryn Stoner, political scientist at Stanford University.

The question that remains, however, is, what is Russia’s endgame? And what does this apparent creeping of media power in those regions mean in an age with a shifting world order?

‘Not all crazy conspiracy theorists’

“[Countries outside the West are] very fertile territory intellectually, culturally, and ideologically [because of their] residual anti-American, anti-Western, and anti-imperial sentiments,” says Stephen Hutchings, a professor of Russian Studies at the University of Manchester.

Russian propaganda, he argues, is also spread smartly: its content is calibrated to cater to specific audiences, even if it means adopting different ideological stances in different regions.

KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV/AFP via Getty Images

KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV/AFP via Getty ImagesTake the perception of RT. In the West it is often seen as a “Russian state actor and propagator of disinformation,” he says. In other parts of the world, however, it is often regarded as a legitimate broadcaster with its own editorial line.

This makes viewers susceptible to believing it – “not all crazy conspiracy theorists who naively fall for disinformation”.

This is how Dr Rhys Crilley puts it. He is a lecturer in international relations at the University of Glasgow, and believes that RT’s coverage of the world can appeal to broad audiences – “people who are rightly concerned about global injustices, or events that they perceive the West to be involved in perpetrating”.

‘A very careful manipulation’

On the surface, RT’s international site looks like a standard news website and it reports some stories accurately. “[It’s] a very careful manipulation”, argues Dr Precious Chatterje-Doody, senior lecturer in Politics and International Studies at The Open University, who wrote a book on RT with Prof Hutchings, Dr Crilley and others.

She and other colleagues analysed RT’s international news bulletins covering a period of two years between May 2017 and May 2019, and concluded that its curation of stories (what it chose to cover and what it left out) fitted certain narratives.

For example, the researchers found that social unrest was prioritised as a topic to report on when it happened in European countries, whereas one of the frequent preferences in the coverage of Russian domestic affairs was the country’s military exercises.

The broadcaster also makes explicit false claims, such as portraying Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 as a peaceful “reunification”, denying clear evidence of military involvement. It has systematically denied evidence of Russian war crimes committed in Ukraine since the full-scale invasion in 2022.

SERGEI BOBYLYOV /AFP via Getty

SERGEI BOBYLYOV /AFP via GettyRT has also published stories with commentators blaming Ukraine for shooting down Malaysia airlines flight MH17 in July 2014. (The UN aviation body has concluded that the Russian Federation is responsible for the downing and international investigators found that a missile system transported from Russia to occupied eastern Ukraine had been used by Russians and pro-Russian separatists to hit it.)

What was striking was the view of audiences on this coverage.

Between 2018 and 2022, the researchers interviewed 109 people who watched RT in the UK before it had its licence to broadcast revoked by media regulator Ofcom. Dr Chatterje-Doody says she observed that many said they felt that “RT is biased” but that they had the tools to discern what was truthful from what was not.

However, based on her research, she warned: “[The audience] is not necessarily aware of the precise ways in which RT is biased and where the dishonesty of the coverage comes from.”

Why Russia has renewed focus on Africa

Russian state media’s biggest recent expansion is in Africa, according to Prof Hutchings.

In February, Russian authorities travelled to Ethiopia for the launch of a new editorial centre for Sputnik. Sputnik already broadcasts across parts of Africa in English and French languages, and has expanded to include Amharic, one of the official languages of Ethiopia.

RT has also reoriented its French-language channel to target French-speaking African nations, along with redirecting funding from projects in London, Paris, Berlin and the US to the continent, according to RT’s editor-in-chief.

MLADEN ANTONOV /AFP via Getty

MLADEN ANTONOV /AFP via GettyLast year Russian state media claimed that RT had seven bureaux in Africa, although this cannot be independently verified.

Many Africans already have friendly views towards Russia – anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist sentiment, together with the legacy of Soviet support for liberation movements during the Cold War made it relatively common.

With this new focus, Russia hopes to undermine Western influence, build support for its actions, and build economic ties, argues Dr Crilley.

Inside RT’s course for African reporters

When RT launched its first online course aimed at African reporters and bloggers, the BBC’s Global Disinformation Unit joined it to find out more.

“We are one of the best in fact-checking and have never been caught distributing false information,” RT’s general director Alexey Nikolov told students.

One lesson examined how to debunk misinformation. The instructor stated a chemical weapons attack in the Syrian city of Douma in 2018, by the Russian-backed Assad regime, was a “canonical example of fake news”, ignoring findings of a two-year investigation by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons confirming the attacks were carried out by the Syrian Air Force.

The host also dismissed the mass killing of Ukrainian civilians by Russian forces in the Ukrainian town of Bucha in 2022, calling it “the most well-known fake”. (This, despite overwhelming UN and independent evidence blaming Russian forces.)

Speaking to those who took part after the course, many seemed unperturbed by this – some told the BBC they believed RT was a standard international TV broadcaster, comparable to CNN or Al Jazeera.

When we interviewed an Ethiopian journalist in December 2024, they echoed RT’s claims by calling the Bucha killings a “staged event”. Their social media profile picture was a photograph of Putin.

A journalist from Sierra Leone acknowledged the risks of misinformation and disinformation but, at the time, added that every media institution has its own “news value and style”.

From the Middle East to Latin America

In the Middle East, Russian state media like RT Arabic and Sputnik Arabic are tailoring their coverage of the Israel-Gaza war to appeal to pro-Palestinian audiences, according to Prof Hutchings.

Elsewhere, including in Latin America, RT is also attempting to expand its reach.

RT is available for free in 10 countries in the region according to its website. Argentina, Mexico, and Venezuela are among them. It’s also on cable television in 10 other countries.

Offering international news in Spanish in free-to-air television is “part of its success,” says Dr Armando Chaguaceda, a Cuban-Mexican historian and political scientist, who is a researcher from the think tank, Government and Political Analysis (focused on civic education and the promotion of democratic culture).

REUTERS/Dado Ruvic

REUTERS/Dado RuvicAnd although RT has been banned on YouTube around the world, since March 2022, it still creeps its way onto the platform in some places.

In Argentina, 52-year old carpenter Aníbal Baigorria records TV reports from RT and uploads them to his YouTube channel, along with his reactions.

“Here in Buenos Aires the news focuses too much on the city,” he argues. “RT gives an overview of all the places in Latin America and, of course, global news.”

“Everyone has the right to decide what they believe is true.”

Understanding the impact

Ultimately, it’s difficult to quantify the impact of Russian state-backed media around the world.

RT claims to be available to more than 900 million TV viewers in more than 100 countries and says its content attracted 23 billion online views in 2024.

But, as Dr Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, professor of communication at the University of Copenhagen, points out: “Availability is not meaningful measure of audience size.”

He also argues that the 900 million viewers figure is “extremely unlikely” and describes online views as a vague and easily manipulated metric.

Dr Chatterje-Doody agrees that assessing the direct impact is hard. But she points to one case which might suggest some success for Russia. In Africa’s Sahel region, which extends from Senegal eastward to Sudan, Russia has played significant military roles “with relatively little public resistance”, even considering the challenging landscape. (It has entrenched itself by supporting military juntas in countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.)

Another narrative that has stuck has been Russia’s justification for the invasion of Ukraine. Russia has long framed Nato’s eastward expansion and Ukraine’s growing ties with the alliance as a key reason for its full-scale invasion, claiming it posed a “security threat” and that Russia acted in “self-defence”. Though widely debunked in the West, this false claim lingered across the Global South.

Misha Friedman/Getty Images

Misha Friedman/Getty Images“The idea… is a pretty well-received narrative, especially in academic circles, in Mexico and in Latin America in general,” says Dr Chaguaceda of the Nato expansion argument.

Some Global South leaders have been hesitant in condemning the Russian war against Ukraine. In the first UN General Assembly vote after the full-scale invasion in 2022, an overwhelming majority of countries condemned the war, but 52 countries either voted against the resolutions, formerly registered their abstention, or refrained from voting. Among them, Bolivia, Mali, Nicaragua, South Africa and Uganda.

RONALDO SCHEMIDT/AFP via Getty Images

RONALDO SCHEMIDT/AFP via Getty ImagesDr Crilley has his own take on what Russia’s endgame is.

“[The Kremlin is trying] to reduce Russia’s relative isolation on the world stage by portraying Russia as a fellow victim of ‘Western’ aggression and a defender of the Global South.”

The risk, he warns, “is that RT and other Russian disinformation efforts prey on and exploit the weaknesses of liberal democracy, while normalising Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, and presenting Russia not as an authoritarian state but as some sort of benign power in global politics.”

Asked for a response to the allegations raised in this article, RT said: “We are indeed expanding around the world.”

They declined to comment further on specific points.

Sputnik did not respond to requests for comment.

Ultimately, Prof Hutchings believes we should all be concerned about Russian state activities – particularly in the context of the future of the global world order and democracy.

He believes the West is taking its “eye off the ball” by cutting media funding and “leaving the field open to the likes of Russia Today.”

“There’s a lot to play for and a lot to lose… And Russia is winning ground – but the battle is not lost.”

Top image credit: MLADEN ANTONOV/AFP via Getty

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.