Tim WhewellPresenter of A People’s History of Gaza

Tim WhewellPresenter of A People’s History of Gaza BBC

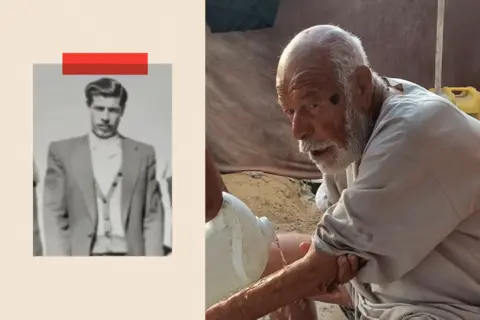

BBC“I rode away on a camel with my grandmother, along a sandy road, and I started to cry.” Ayish Younis is describing the worst moment of his life – he still regards it as such, even though it was 77 years ago, and he’s lived through many horrors since.

It was 1948, the first Arab-Israeli war was raging, and Ayish was 12. He and his whole extended family were fleeing their homes in the village of Barbara – famed for its grapes, wheat, corn and barley – in what had been British-ruled Palestine.

“We were scared for our lives,” Ayish says. “On our own, we had no means to fight the Jews, so we all started to leave.”

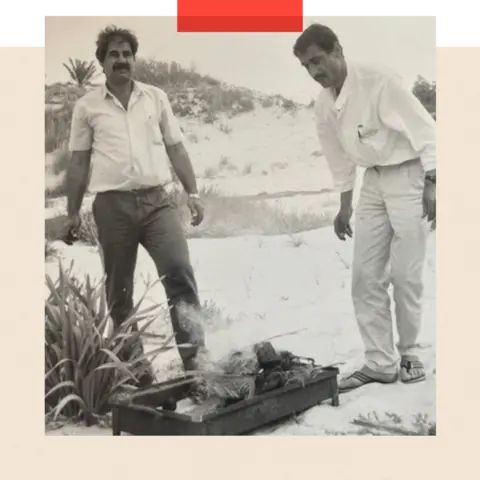

Ahmed Younis family archive/BBC

Ahmed Younis family archive/BBCThe camel took Ayish and his grandmother seven miles south from Barbara, to an area held by Egypt that would become known as the Gaza Strip. It was just 25 miles long and a few miles wide, and had just become occupied by Egyptian forces.

In all an estimated 700,000 Palestinians lost their homes and became refugees as a result of the war of 1948-49; around 200,000 are believed to have crowded into that tiny coastal corridor.

“We had bits of wood which we propped against the walls of a building to make a shelter,” Ayish says.

Later, they moved into one of the huge tented camps established by the United Nations.

Today, aged 89, Ayish is again living in a tent in Al-Mawasi near Khan Younis.

In May last year, seven months into the two-year war between Israel and Hamas, Ayish was forced to leave his home in the southern Gaza city of Rafah after an evacuation order from the Israeli military.

The four-storey house, divided into several apartments, that he had shared with his children and their families, was destroyed by what he believes may have been Israeli tank-fire.

Now, home is a small white canvas tent just a few metres across.

Other members of the family are in neighbouring tents. They have all had to cook on an open fire. With no access to running water they wash using canned water, which is scarce and as a result expensive.

“We returned to what we started with, we returned back to tents, and we still don’t know how long we will be here,” he says, sitting in a plastic chair on the bare sand outside his tent, with clothes drying on a washing line nearby.

A walking frame is propped beside him, as he moves with difficulty. But he still speaks in the crystal-clear, melodious Arabic of one who studied literature, and recited the Quran daily as the imam of a local mosque.

“After we left Barbara and lived in a tent, we eventually succeeded in building a house. But now, the situation is more than a catastrophe. I don’t know what the future holds, and whether we will ever be able to rebuild our house again.”

“And in the end I just want to go back to Barbara, with my whole extended family, and again taste the fruit that I remember from there.”

On 9 October, Israel and Hamas agreed to the first phase of a ceasefire and hostage release deal. The remaining living 20 Hamas-held hostages were returned to Israel and Israel released nearly 2,000 Palestinian detainees and prisoners.

Yet despite widespread rejoicing over the ceasefire, Ayish is not optimistic about the long-term prospects for Gaza.

“I hope the peace will spread and it will be calm,” he says. “But I believe the Israelis will do whatever they like.”

Under the agreement for the first stage of the ceasefire, Israel will retain control of more than half the Gaza Strip, including Rafah.

One question Ayish, his family and all Gazans are pondering is whether their homeland will ever be successfully rebuilt.

My 18 children and 79 grandchildren

Back in 1948, the Egyptian army had been one of five Arab armies that had invaded the British-controlled territory of Mandate Palestine the day after the establishment of a Jewish state, Israel. But they soon withdrew, defeated, from Barbara, prompting Ayish’s decision to flee.

Ayish became a teacher when he was 19, and gained a literature degree in Cairo under a scholarship programme.

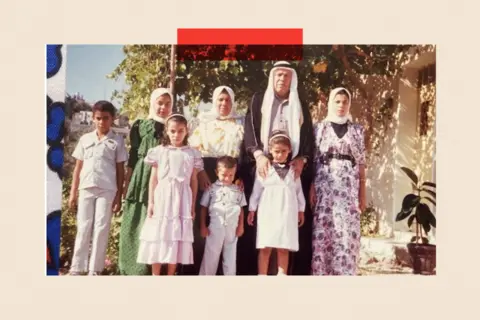

The best moment of his life, he says, was when he married his wife Khadija. Together they had 18 children. That, according to a newspaper article that once featured him, is a record – the largest number of children from the same mother and father of any Palestinian family.

Today, he has 79 grandchildren, two of them born in the last few months.

Ahmed Younis family archive

Ahmed Younis family archiveThe family would move from their first tent to a simple three-room cement house with an asbestos roof in the refugee camp, which they later extended to nine rooms – thanks partly to wages earned in Israel.

When the border between Israel and Gaza opened, and Ayish’s eldest son Ahmed was one of many Palestinians who took advantage of that, working in an Israeli restaurant during his holidays, while studying medicine in Egypt.

“During that time, in Israel, people were paid very well. And this is the period of time where the Palestinians made most of their money,” he says.

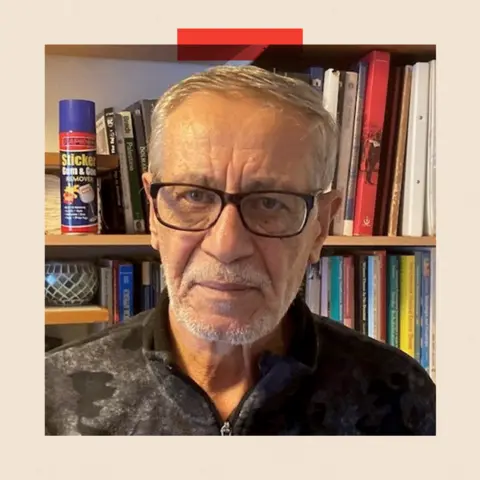

All but one of Ayish’s children gained university degrees. They became engineers, nurses, teachers. Several moved abroad. Five are in Gulf countries and Ahmed, a specialist in spinal cord injuries, now lives in London. Many other Gazan families are similarly scattered.

The Younis family, like many Gazans, wanted nothing to do with politics. Ayish became an imam at a Rafah mosque – and a local headman (or mukhtar) responsible for settling disputes, just as his uncle had been years earlier in the village of Barbara.

He was not appointed by the government – but he says that both Hamas and the Fatah political movement, the dominant party in the Palestinian authority, respected him.

That didn’t save the family from tragedy, though, during the street battles of 2007, when Fatah and Hamas fought for control of the Strip. Ayish’s daughter Fadwa was killed in cross-fire as she sat in a car.

The rest of the family survived through wars between Hamas and Israel in 2008, 2012, 2014 – as well as the devastating war triggered by the deadly Hamas attack on Israel on 7 October 2023.

Then came that evacuation order by the Israeli military who said they were carrying out operations against Hamas in the area, forcing them to leave their Rafah home and over a year spent living in makeshift tents.

Ayish’s life has come full circle since 1948. But his greatest desire is to go even further back in time, to return to the village, now in Israel, which he last saw when he was 12 – even though it no longer exists.

Apart from clothes, cooking pots and a few other essentials, the only possessions he has with him in his tent are the precious title deeds to his ancestral land in Barbara.

‘I don’t believe Gaza has any future’

Thoughts are now turning to the reconstruction of Gaza.

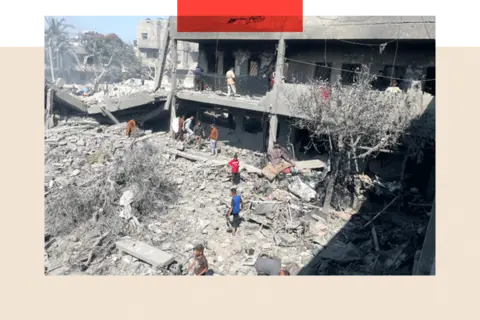

But Ayish believes the extent of the destruction – of infrastructure, schools and health services – is so great that it cannot be fully repaired, even with the help of the international community.

“I don’t believe Gaza has any future,” he says.

He believes that his grandchildren could play a role in the reconstruction of Gaza if the ceasefire is fully implemented, but he does not believe they will be able to find jobs in the territory as good as those they have or could get abroad.

His son Haritha, a graduate in Arabic language who has four daughters and a son, is also living in a tent. “An entire generation has been destroyed by this war.

“We are unable to comprehend it,” he says.

Ahmed Younis family archive

Ahmed Younis family archive“We used to hear from our fathers and grandfathers about the 1948 war and how difficult the displacement was, but there is no comparison between 1948 and what happened in this war.

“We hope that our children will have a role in rebuilding, but as Palestinians, do we have the capacity on our own to rebuild the schools? Will donor countries play a role in that?”

“My daughter has gone through two years of war without schooling, and for two years before that schools were closed because of Covid,” he continues. “I used to work in a clothing store, but it was destroyed.

“We don’t know how things will unfold or how we will have a source of income. There are so many questions we have no answers for. We simply don’t know what the future holds.”

Another of Ayish’s sons, Nizar, a trained nurse, who lives in a tent nearby, agrees. He believes Gaza’s problems are so great that the youngest generation of the family will not be able to play much role, despite their high level of education.

“The situation is unbearable,” he says. “We hope that life will return to how it was before the war. But the destruction is massive – total destruction of buildings and infrastructure, psychological devastation within the community, and the destruction of universities.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAyish’s eldest son Ahmed, in London, meanwhile reflects on how it took the family more than 30 years to build their former home into what it eventually became – as money was saved over the years it was expanded, he explains.

“Do I have another 30 years to work and try to help and support my family? This is really the situation all the time – every 10 to 15 years, people lose everything and they come back to square one.”

And yet he still dreams of living in Rafah again when he retires. “My brothers in the Gulf bought land in Rafah to come back and settle as well. My son, and my nephews and nieces – they want to go back.”

With a pause, he adds: “By nature, I’m very optimistic, because I know how determined our Gaza people are. Trust me, they will go back and start to rebuild their lives again.

“The hope is always in the new generation to rebuild.”

Top picture credit: AFP via Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.