Cherylann MollanBBC News, Mumbai

BBC

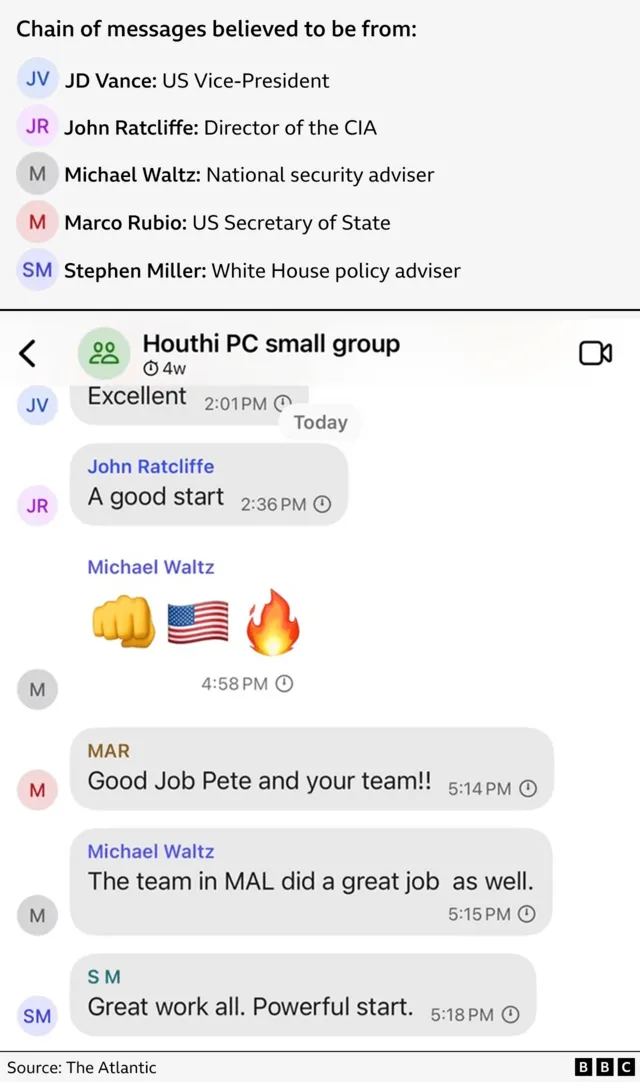

BBCIn an old, neo-gothic building in Fort, an upmarket area in India’s financial capital Mumbai, is a run-down office that produces one of country’s oldest and most prominent Parsi magazines – Parsiana.

The magazine was started in 1964 by Pestonji Warden, a Parsi doctor who also dabbled in the sandalwood trade, to chronicle the community in the city.

Since then, the magazine has grown in subscribers and reach. For many Parsis, it has offered a window into the goings-on in the community, helping members across the world feel connected and seen as their numbers dwindled and dispersed.

After 60 years, Parsiana will shut this October due to dwindling subscribers, lack of funds, and no successor to run it.

The news has saddened not just subscribers but also those who knew of the magazine’s legacy.

“It’s like the end of an era,” says Sushant Singh, 18, a student. “We used to joke about how you weren’t a “true Parsi” if you didn’t know about Parsiana or wax eloquent about it.”

Since the news of the magazine’s closing was announced in one of its editorials in August, tributes have been pouring in.

In its September edition, a reader in Mumbai writes: “To think that such a small community as ours could be chronicled with such diligence and passion seems a daunting endevour. However, Parsiana proved more than equal to the task.”

Another reader, based in Pakistan says that the magazine has been “more than a publication; it has been a companion and bridge connecting Zoroastrians across the world”.

A Washington-based reader praised the magazine for keeping the community informed “but also bringing a touch of realism on contentious issues”.

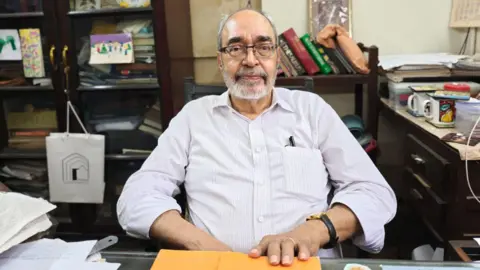

Jehangir Patel, 80, who has led the magazine since buying it for just one rupee in 1973, says he always wanted it to be a “journalistic endeavour.”

When Warden started the magazine as a monthly, it only carried essays by Parsis or Warden’s medical writings.

After taking over, Mr Patel turned it into a fortnightly with reported stories, sharp columns, and illustrations that tackled sensitive Parsi issues with honesty and humour.

He hired and trained journalists, set up a subscription model and eventually, turned the black-and-white journal into colour.

Mr Patel recalls his first story after taking over the magazine; it was about the high divorce rate within the community.

“Nobody expected to read something like that in Parsiana. It was a bit shocking for the community.”

In 1987, the magazine broke new ground by publishing interfaith matrimonial ads – a bold move in a community known for strict endogamy.

“The announcements created a furore in the community. Many readers wrote to us, asking us to discontinue the practice. But we didn’t,” Mr Patel says.

He says Parsiana never shied from controversy, always offering multiple perspectives, and over the years spotlighted issues like the community’s dwindling population and the decline of the Towers of Silence – a place where the Parsis bury their dead.

The journal also chronicled community achievements, key social and religious events, and new Parsi institutions. In May, Parsiana covered the inauguration of the Alpaiwalla Museum in Mumbai – the only Parsi museum in the world.

Now the 15-member team, many in their 60s and 70s who joined under Patel, is preparing to end both the magazine and their journalism careers.

“There’s a sense of tiredness mixed with the sadness,” Mr Patel says. “We’ve been doing this for a long time,” he adds.

The office, stacked with old editions, shows its age with peeling paint and crumbling ceilings. It is housed in a former Parsi hospital that has stood vacant for four decades.

Mr Patel says the team has no grand plans for their last day, but upcoming issues will feature stories commemorating Parsiana’s long journey and legacy.

As for the team, Mr Patel says they might have a lunch in office. No cake. No celebrations.

“It’s a sad occasion,” Mr Patel says. “I don’t think we’ll feel like celebrating.”

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.