West Africa analyst

Reuters

ReutersEven a stellar international business career cannot prepare you for the hard realities of politics in Ivory Coast, where some are questioning the democratic credentials of the West African nation most famous for being the producer of much of the world’s cocoa and some of its finest footballers.

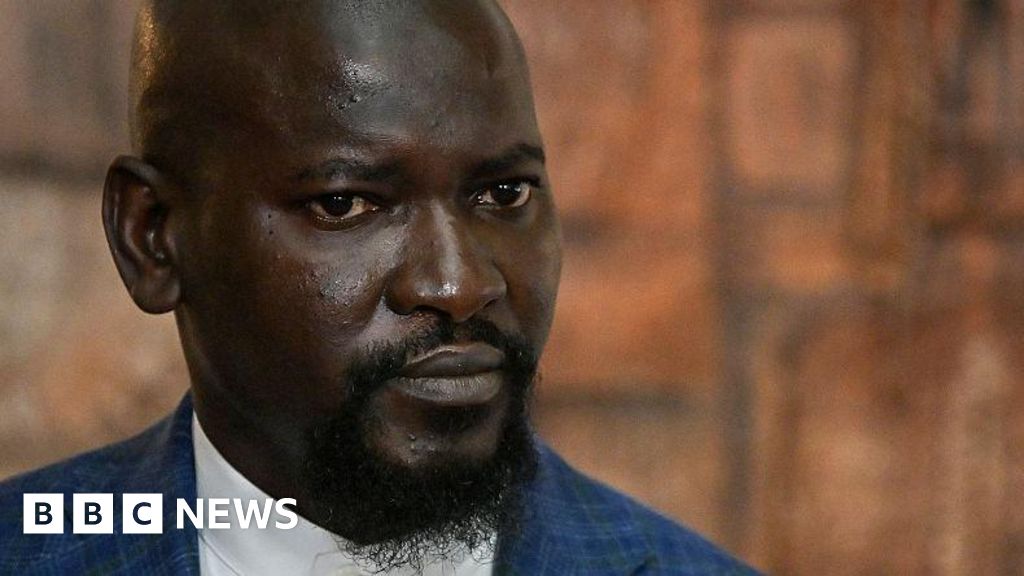

That is the painful lesson Tidjane Thiam is learning as he waits to see whether deal-making in the corridors of power and popular pressure from the street can rescue his bid to become president of Ivory Coast.

Seemingly relentless progress towards the election set for this October came to a juddering halt on 22 April when a judge ruled that the 62-year-old had lost his Ivorian citizenship by taking French nationality decades previously and not revoking it until too late to qualify for this year’s vote.

Moving back to Ivory Coast in 2022 after more than two decades in global finance, Thiam had immediately been seen as a potential contender to succeed current head of state Alassane Ouattara who, at 83, is now in the final year of his third term of office.

A scion of a traditional noble family and a great nephew of the country’s revered founding President, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, he had impressed as a top government official and minister in the 1990s, overseeing infrastructure development and radical economic reforms.

A military coup then pushed Thiam to seek a fresh career abroad, which culminated in high-profile stints as chief executive of UK insurance giant Prudential and then the banking group Credit Suisse.

But returning home at last, three years ago, he embarked on a steady advance towards the next Ivorian presidential election.

After the death in 2023 of former President Henri Konan Bédié, long-serving leader of the opposition Democratic Party of Ivory Coast (PDCI), Thiam was perfectly positioned to take his place and then on 17 April this year he was chosen as the party’s candidate for the upcoming presidential race.

That was no guarantee of victory, and especially if – as seems quite plausible Ouattara opts to run for a fourth term, backed by all the assets and advantages of incumbency and a track record of four successive years of annual economic growth above 6%.

However, Thiam stood out as the prime alternative.

AFP

AFPAs an opponent of the ruling Rally of Houphouëtists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP), he offered Ivorian voters the chance to change their government.

Yet with his centrist politics and solid technocratic credentials, his candidacy offered reassuring competence and the prospect of continuing the impressive economic progress that Ouattara has piloted since 2011.

Now that potential trajectory is blocked. If the court decision stands – and Ivorian law offers no option of appeal for this particular issue – Thiam will be out of October’s contest.

It is a race from which past court convictions have already excluded three other prominent opposition figures – former President Laurent Gbagbo, former Prime Minister Guillaume Soro and a former minister, Charles Blé Goudé – all central actors in the political crises and civil conflicts that brutally paralysed the progress of Ivory Coast between 1999 and 2011.

The prospect now is that Ouattara or any chosen RHDP successor candidate will approach the election without facing any heavyweight political challenge.

That can only deepen Ivorians’ already widespread popular disillusionment with the country’s political establishment.

This is against the wider context of a West Africa where the radical anti-politics rhetoric of the soldiers who have seized power in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger already finds a sympathetic audience among many disenchanted young people.

That really matters in societies where, typically, three-quarters of the population is under 35.

AFP

AFPAmidst this crisis for West African democracy, there have been some moments of encouragement.

In Liberia in 2023 and in Senegal and Ghana last year, incumbent governments were voted out, in free and fair elections whose results were accepted by all contestants without argument.

The Senegalese result, in particular, owed much to the massive enthusiastic mobilisation of young people.

Many hoped that Ivory Coast could offer a further positive example of democratic choice and the offer of change, and an example that might be all the more influential because the country is a prosperous regional powerhouse.

It is the economic engine of the CFA franc single currency bloc and besides the cocoa industry, it is also a key hub for business services and finance and a leading political voice in the regional grouping, the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas).

What happens in Ivory Coast really matters and is widely noticed, across West Africa and indeed, also right across francophone Africa more generally.

Ouattara is one of the continent’s most prominent statesmen, commanding broad respect internationally too.

And yet now the run-up to the country’s crucial next presidential election has become ensnared in a return version of the identity politics that so soured the bitter disputes and instability of the 1990s and 2000s.

Back then, the governments of first Bédié and then Gbagbo used the contentious “ivoirité”, meaning “Ivorian-ness” law to shut Ouattara out of standing for the presidency on the grounds that his family allegedly had foreign origins.

It was only in 2007 that the government scrapped the ban on his candidacy and only in 2016 – when he was already in office – that a new constitution at last ended the requirement that the stated parents of presidential candidates be native-born Ivorians.

AFP

AFPThe poisonous mobilisation of identity issues had been a major contributing factor to the civil wars, street violence and northern separatist partition that brutally scarred Ivory Coast for more than a decade, up to 2011, at a cost of thousands of lives.

Today the country feels far from such large-scale conflict.

There is no popular appetite for a return to confrontation and politicians are staying well away from the incendiary rhetoric of the past.

But the Thiam saga shows how identity issues, even in a more legalistic form and in this hopefully more peaceful era, can still weigh heavily.

Ivory Coast only permits dual nationality under certain limited conditions.

So in its 22 April ruling, an Abidjan court declared that, under the terms of a little-used post-independence law, Thiam had automatically lost his Ivorian citizenship almost four decades ago when he acquired French nationality – after several years’ study in Paris.

Although he officially surrendered that this February, and thus automatically recovered his original citizenship, this was too late for inclusion on this year’s register of eligible voters or candidates.

In vain, his lawyers had argued that, through his father, Thiam had French nationality from birth – which, if accepted, would exempt him from the dual nationality ban.

Seeking to highlight the absurdity and inconsistencies of the situation, he argued that, logically, the country should now hand back its prized 2024 Africa Cup of Nations football title because many of the players also have French nationality.

“If we apply the law the way [that] they just applied it to me, we have to give the cup back to Nigeria – because half of the team was not Ivorian,” he told the BBC.

And Thursday could bring yet another setback in a scheduled court hearing where a judge may now rule that Thiam cannot, as a non-national, lead the PDCI.

The past two weeks have seen continuing political and legal debate over this whole saga, with the Thiam camp hoping that a combination of popular pressure and discreet political negotiation will lead to a compromise that lets him back into the presidential race, perhaps along with the other excluded contenders.

And Ouattara, should he chose not to run, might want to safeguard his impressive track record and secure his international reputation by intervening with some kind of deal that allows Thiam to run.

With months to go before the polls, there is still time for that. But no-one is counting on it.

Paul Melly is a consulting fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC