Soho House

Soho HouseFor decades, the Indian elite have sought escape in Raj-era private clubs and gymkhanas, scattered around the swankiest neighbourhoods in the country’s big cities, hillside resorts and cantonment towns.

Access to these quintessentially “English” enclaves, with their bellboys, butlers, dark mahogany interiors and rigid dress codes, has been reserved for the privileged; the old moneyed who roam the corridors of power – think business tycoons, senior bureaucrats, erstwhile royals, politicians or officers of the armed forces.

This is where India’s rich and powerful have hobnobbed for years, building social capital over cigars or squash and brokering business deals during golf sessions. Today, these spaces can feel strangely anachronistic – relics of a bygone era in a country eager to shed its colonial past.

As Asia’s third largest economy breeds a new generation of wealth creators, a more modern and less formal avatar of the private members-only club – that reflects the sweeping economic and demographic changes under way in India – is emerging. This is where the newly well-heeled are hanging out and doing business.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

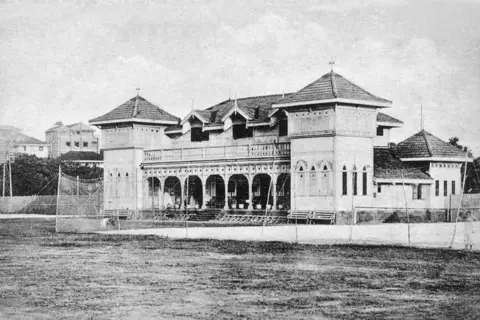

Getty ImagesDemand for such spaces is strong enough for the international chain Soho House to plan two new launches in the capital Delhi and in south Mumbai in the coming months. Their first offering – an ocean-facing club on Mumbai’s iconic Juhu Beach – opened six years ago and is wildly successful.

The chain is one of a host of new club entrants vying to cater to a market that is booming in India.

Soho House started in London in the mid-90s as an antidote to the upscale gentlemen’s clubs that lined Pall Mall. It came in as a refreshingly new concept: a more relaxed club for creators, thinkers and creative entrepreneurs, who might have felt like they didn’t belong in the enclaves of the old aristocracy.

Thirty years later, India’s flourishing tech-driven economy of start-ups and creators has birthed a nouveau riche that’s afforded Soho House exactly another such market opportunity.

“There’s growth in India’s young wealth, and young entrepreneurs really need a foundation to platform themselves,” Kelly Wardingham, Soho House’s Asia regional director, told the BBC. The “new wealthy require different things” from what the traditional gymkhanas offer.

Unlike the old clubs, Soho House does not either “shut off” or let in people based on their family legacy, status, wealth or gender, she says. Members use the space as a haven to escape the bustle of Mumbai, with its rooftop pool, gym and private screening rooms as well as a plethora of gourmet food options. But they also use it to drive value from a diverse community of potential mentors and investors, or to learn new skills and attend events and seminars.

Reema Maya, a young filmmaker, says her membership of the house in Mumbai – a city “where one is always jostling for space and a quiet corner in a cramped cafe” – has given her rare access to the movers and shakers of Mumbai’s film industry – which might otherwise have been impossible for someone like her “without generational privilege”.

In fact, for years, traditional gymkhanas were closed off for the creative community. The famous Bollywood actor, the late Feroz Khan, once asked a gymkhana club in Mumbai for membership, only to be politely refused, as they didn’t admit actors.

Khan, taken aback by their snootiness, is said to have quipped, “If you’d watched my movies, you would know I am not much of an actor.”

By contrast, Soho House proudly flaunts Bollywood star Ali Fazal, a member, on its in-house magazine cover.

Soho House

Soho HouseBut beyond just a more modern, democratic ethos, high demand for these clubs is also a factor of the limited supply of the traditional gymkhanas, which are still very sought after.

Waiting queues at most of them can extend “up to many years,” and supply hasn’t caught up to serve the country’s “new crop of self-made businessmen, creative geniuses and high-flying corporate honchos”, according to Ankit Kansal of Axon Developers, which recently released a report on the rise of new members-only clubs.

This mismatch has led to more than two dozen new club entrants – including independent ones like Quorum and BVLD, as well as those backed by global hospitality brands like St Regis and Four Seasons – opening in India. At least half a dozen more are on their way in the next few years, according to Axon Developers.

This market, the report says, is growing at nearly 10% every year, with Covid having become a big turning point, as the wealthy chose to avoid public spaces.

While these spaces mark significant shifts, with their progressive membership policies and patronage of the arts, literary and independent music scene they are very much still “sanctums of modern luxury”, says Axon, with admission given out by invite only or through referrals, and costing several times more than the monthly income of most Indians.

At Soho House for instance, annual membership is 320,000 Indian rupees ($3,700; $2,775) – beyond what most people can afford.

What’s changed is that membership is based on personal accomplishment and future potential rather than family pedigree. A new self-made elite has replaced the old inheritors – but access remains largely out of reach for the average middle-class Indian.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesIn a way the rising take-up for these memberships reflects India’s broader post-liberalisation growth story – when the country opened up to the world and discarded its socialist moorings.

Growth galloped, but the rich became the biggest beneficiaries, growing even richer as inequality reached gaping proportions. It’s why the country’s luxury market has boomed, even as the high street struggles with tepid demand, with most Indians without money to spend on anything beyond the basics.

But growing numbers of newly-minted rich present a big business opportunity.

India’s 797,000 high-net worth individuals are set to double in number within a couple of years – a fraction of a population of 1.4 billion, but enough to drive future growth for those building new playgrounds for the wealthy to unwind, network and live the high life.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.