BBC Afghan Service, in Kabul

BBC

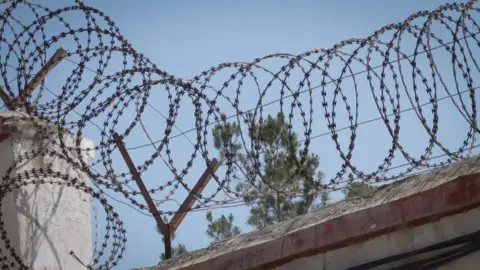

BBCHigh on a hill in the west of the Afghan capital, Kabul, behind a steel gate topped with barbed wire, lies a place few locals speak of, and even fewer visit.

The women’s wing of a mental health centre run by the Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS) is the largest of only a handful of facilities in the country dedicated to helping women with mental illnesses.

Locals call it Qala, or the fortress.

The BBC gained exclusive access to the crowded centre where staff find it difficult to cope with the 104 women currently within its walls.

Among them are women like Mariam* who says she is a victim of domestic violence.

Thought to be in her mid-20s, she’s been here for nine years, after enduring what she describes as abuse and neglect by her family, followed by a period of homelessness.

“My brothers used to beat me whenever I visited a neighbour’s house,” she alleges. Her family did not want to let her out of the house alone, she says, because of a cultural belief that young girls should not leave the house without supervision.

Eventually, her brothers appeared to have kicked her out, forcing her to live on the streets at a young age. It was here a woman found her and, apparently concerned about her mental health, brought her to the centre.

Despite her story, Mariam’s smile is constantly radiant. She is often seen singing, and is one of the few patients allowed to work around the building, volunteering to help with cleaning.

She is ready – and willing – to be discharged.

But she cannot leave because she has nowhere to go.

“I don’t expect to return to my father and mother. I want to marry someone here in Kabul, because even if I go back home, they’ll just abandon me again,” Mariam says.

As she can’t return to her abusive family, she is effectively trapped in the facility.

In Afghanistan, strict Taliban regulations and deeply-rooted patriarchal traditions make it nearly impossible for women to live independently. Women are legally and socially required to have a male guardian for travel, work, or even accessing many services, and most economic opportunities are closed to them.

Generations of gender inequality, limited education, and restricted employment have left many women financially dependent on male breadwinners, reinforcing a cycle where survival often hinges on male relatives.

Sat on a bed in one of the dormitories is Habiba.

The 28-year-old says she was brought to the centre by her husband, who was forcing her out of the family home after he married again.

Like Mariam, she now has nowhere else to go. She too is ready to be released, but her husband will not take her back, and her widowed mother cannot support her either.

Her three sons now live with an uncle. They visited her initially, but Habiba hasn’t seen them this year; without access to a phone, she cannot even make contact.

“I want to be reunited with my children,” she says.

Their stories are far from unique at the centre, where our visit, including conversations with staff and patients, is overseen by officials from the Taliban government.

Some patients have been here for 35 to 40 years, says Saleema Halib, a psychotherapist at the centre.

“Some have been completely abandoned by their families. No-one comes to visit, and they end up living and dying here.”

Years of conflict has left its mark on the mental health of many Afghans, especially women, and the issue is often poorly understood and subject to stigma.

In response to a recent UN report on the worsening situation of women’s rights in Afghanistan, Hamdullah Fitrat, Taliban government’s deputy spokesperson, told the BBC that their government did not allow any violence against women and they have “ensured women’s rights in Afghanistan”.

But UN data released in 2024 points to a worsening mental health crisis linked to the Taliban’s crackdown on women’s rights: 68% of women surveyed reported having “bad” or “very bad” mental health.

Services are struggling to cope, both inside and outside the centre, which has seen a several-fold increase in patients over the last four years, and now has a waiting list.

“Mental illness, especially depression, is very common in our society,” says Dr Abdul Wali Utmanzai, a senior psychiatrist at a nearby hospital in Kabul, also run by ARCS.

He says he sees up to 50 outpatients a day from different provinces, most of them women: “They face severe economic pressure. Many have no male relative to provide for them – 80% of my patients are young women with family issues.”

The Taliban government says it is committed to providing health services. But with restrictions on women’s movement without a male chaperon, many cannot seek help.

All of this makes it more difficult for women like Mariam and Habiba to leave – and the longer they stay, the fewer places there are for those who say they desperately need help.

One family had been trying for a year to admit their 16-year-old daughter, Zainab, to the centre, but they were told there were no beds available. She is now one of the youngest patients there.

Until then she had been confined to her home – her ankles shackled to prevent her running away.

It’s not clear what mental health problems Zainab has been experiencing, but she struggles to verbalise her thoughts.

A visibly distressed Feda Mohammad says the police recently found his daughter miles from home.

Zainab had gone missing for days, which is especially dangerous in Afghanistan, where women are not allowed to travel long distances from home without a male guardian.

“She climbs the walls and runs away if we unchain her,” Feda Mohammad explains.

Zainab breaks down into tears every now and then, especially when she sees her mother crying.

Feda Mohammad says they noticed her condition when she was eight. But it worsened after multiple bombings hit her school in April 2022.

“She was thrown against a wall by the blast,” he says. “We helped carry out the wounded and collect the bodies. It was horrific.”

Exactly what would have happened if space hadn’t been found is unclear. Zainab’s father said her repeated attempts to run away were dishonouring him, and he argued it was better for her and her family that she is confined to the centre.

Whether she – like Mariam and Habiba – will now become one of Qala’s abandoned women remains to be seen.

*The names of the patients and their families have been changed throughout