Wedaeli Chibelushi

National Army Museum

National Army MuseumOne day, some 85 years ago, Mutuku Ing’ati left his home in southern Kenya and was never seen again.

The 30-something Mr Ing’ati had disappeared with no explanation – for years his family desperately tried to track him down, following lead after lead that would eventually dry up.

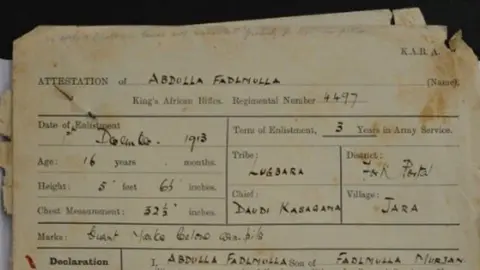

As decades passed, memories of Mr Ing’ati faded. He had no children and many of those close to him passed away. But then, roughly eight decades later, his name re-emerged in British military records.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), which works to commemorate those who died in the two world wars, contacted Mr Ing’ati’s nephew, Benjamin Mutuku, after mining old documents.

He learnt that on the day his uncle left his village, Syamatani, he travelled roughly 180km (110 miles) westwards to Nairobi – the seat of the British colonial government then in control of the country.

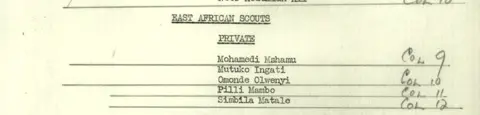

There, he signed up as a private with the East African Scouts, a regiment in the British army that fought in World War Two. The UK recruited millions of men from its empire to fight in both of the 20th Century’s global conflicts in theatres across the world.

Mr Ing’ati responded to the call for recruits – when exactly is not clear – and then on 13 June 1943, he was killed in action, according to the records unearthed by CWGC. Where and how he died is not known.

CWGC/Kenyan Defence Force/British Library

CWGC/Kenyan Defence Force/British LibraryLike thousands of Kenyans who fought in the British army, he died without his family being notified and was buried in a location unknown to this day.

Decades on, as the UK marks Remembrance Sunday to honour those who contributed to the war effort, the sacrifices of many Kenyan soldiers, like Mr Ing’ati, remain unrecognised.

The world knows little of their service and they were not formerly commemorated in the way their white counterparts were.

After all these years, Mr Mutuku was pleased to learn where his uncle had disappeared to and when he died. Despite being born after Mr Ing’ati left the village, Mr Mutuku feels a strong connection to his uncle, from whom he got his name.

“I used to ask my father, where is the person I was named after?” Mr Mutuku, now 67, tells the BBC.

Although he welcomes the fresh information, Mr Mutuku feels angry that his uncle’s body is somewhere out in the world, and not buried in Syamatani.

His family are from the Akamba ethnic group, who believe being laid to rest near the family home is very important.

“I never got a chance to see a tomb where my uncle got buried,” Mr Mutuku says. “I would have liked so much to see that.”

Nellyson Mutuku

Nellyson MutukuThe CWGC is trying to find out where Mr Ing’ati died and where his body is, along with the details of other forgotten Kenyan soldiers.

A search is also on for details about East Africans who fought and died during World War One.

With help from the Kenyan Defence Forces, the CWGC recently unearthed a treasure trove of rare colonial military records in Kenya dating from that conflict. As a result researchers have been able to recover the names and stories of more than 3,000 soldiers who served at that time.

The records, thought to have been destroyed decades ago, concern the King’s African Rifles. Comprised of East African soldiers, the regiment fought against German troops in the region, in what is now Tanzania in World War One, and Japanese troops in what is now Myanmar in World War Two.

“These are not just dusty files – they are personal stories. For many African families, this may be the first time they learn about a relative’s wartime service,” George Hay, a historian at the CWGC, tells the BBC.

For example, there is George Williams, a decorated sergeant major with the Kings African Rifles. Described as 5ft 8in (170cm) with a scar on the right side of his chin, Mr Williams received several medals for gallantry and was recognised as a first-class shot. He died, aged 44, in Mozambique just four months before the war ended.

There are also records for Abdulla Fadlumulla, a Ugandan soldier who enlisted with the King’s African Rifles in 1913, aged only 16. He was killed just 13 months later, while assaulting an enemy position in Tanzania.

CWGC/Kenyan Defence Force/British Library

CWGC/Kenyan Defence Force/British LibraryThe records demonstrate how the wars “touched every fabric in Kenya”, Patrick Abungu, a historian at CWGC’s Kenya office, says.

“Because the narrative is, they went and never came back. And now we are answering those questions: where they went and where [their bodies] could be,” he adds.

The historian wants to answer these questions for thousands of families across Kenya – his own included.

His great uncle, Ogoyi Ogunde, was conscripted into the British army during World War One and never returned home.

“It’s very traumatic to lose a loved one and not know where they are,” he tells the BBC.

“It does not matter how many years go by, people will always look at the gate and hope that he will walk in one day.”

Mr Abungu and the CWGC hope to build memorials to finally commemorate the thousands of soldiers identified from the newly discovered documents.

National Army Museum

National Army MuseumThe organisation also wants the records to help inform Kenya’s school curriculum, so that new generations come to understand the outsized, yet overlooked role Africans played in the world wars.

“The only way any of this matters is that it isn’t coming from people like me saying, ‘This is your history’,” CWGC’s Mr Hay says.

“It’s about people saying, ‘This is our history’ – and using the materials that we’re working with.”

The CWGC will continue recovering the details of Kenyan individuals who served in the British forces until every fallen soldier is commemorated.

“There is no end date… I mean this could go on for 1,000 years,” Mr Abungu says.

“The process that is taking place is ensuring that those thousands of people who went away and never came back… we keep their memories going so that we don’t forget them.”

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC