BBC

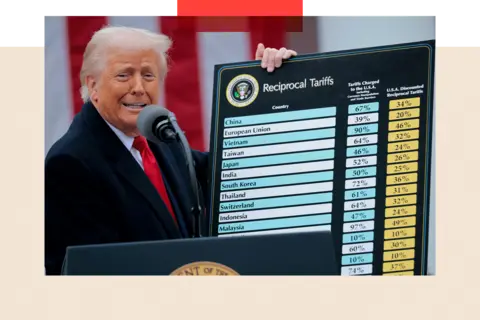

BBCIn April Donald Trump stunned the world by announcing sweeping new import tariffs – only to put most on hold amid the resulting global financial panic.

Four months later, the US president is touting what he claims are a series of victories, having unveiled a handful of deals with trading partners and unilaterally imposed tariffs on others, all without the kind of massive disruptions to the financial markets that his spring attempt triggered.

At least, so far.

Having worked to reorder America’s place in the global economy, Trump is now promising that the US will reap the benefits of new revenue, rekindle domestic manufacturing, and generate hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign investment and purchases.

Whether that turns out to be the case – and whether these actions will have negative consequences – is still very much in doubt.

What is clear so far, however, is that a tide that was (gently) turning on free trade, even ahead of Trump’s second term, has become a wave crashing across the globe. And while it is reshaping the economic landscape, it hasn’t left the kind of wreckage in its wake that some might have predicted – though of course there is often a lag before impact is fully seen.

What’s more, for many countries, this has all served as a wake up call – a need to remain alive to fresh alliances.

And so, while the short term result might be – as Trump sees it – a victory, the impact on his overarching goals is far less certain. As are the long-term repercussions, which could well pan out rather differently for Trump – or the America he leaves behind after his current term.

The ’90 deals in 90 days’ deadline

For all the wrong reasons, 1 August had been ringed on international policymakers’ calendars. Agree new trading terms with the US by then, they’d been warned – or face potentially ruinous tariffs.

While White House trade adviser Peter Navarro predicted “90 deals in 90 days” and Trump offered an optimistic outlook on reaching agreements, the deadline always appeared to be a tall order. And it was.

By the time the end of July rolled around, Trump had only announced about a dozen trade deals – some no more than a page or two long, without the kind of detailed provisions standard in past negotiations.

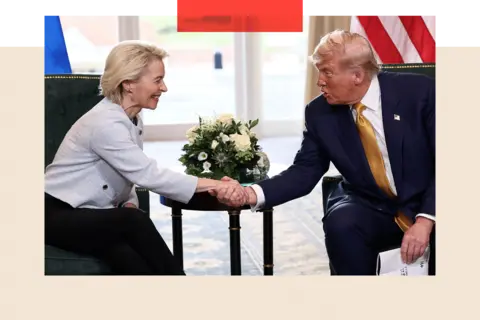

REUTERS/Suzanne Plunkett/Pool

REUTERS/Suzanne Plunkett/PoolThe UK was first off the blocks, perhaps inevitably. Trump’s biggest bugbear is, after all, America’s trade deficit, and trade is in broad balance when it comes to the UK.

While the baseline 10% applied to most British goods may initially have raised eyebrows, it provided a hint of what was to follow – and in the end came as a relief compared to the 15% rate applied to other trading partners such as the EU and Japan, with whom the US has larger deficits; $240bn and $70bn respectively last year alone.

And even those agreements came with strings attached. Those countries that weren’t able to commit to, say, buying more American goods, often faced higher tariffs.

South Korea, Cambodia, Pakistan – as the list grew, and tariff letters were fired off elsewhere, the bulk of American imports are now covered by either an agreement or a presidential decree concluded with a curt “thank you for your attention to this matter”.

Capacity to ‘damage’ the global economy

Much has been revealed as a result of this.

First, the good news. The wrangling of the last few months means the most painful of tariffs, and recession warnings, have been dodged.

The worst fears – in terms of tariff levels and potential economic fallout (for the US and elsewhere) – have not been realised.

JOHN G MABANGLO/EPA/Shutterstock

JOHN G MABANGLO/EPA/ShutterstockSecond, the agreement of tariff terms, however unpalatable, reduced much of the uncertainty (itself wielded by Trump as a powerful economic weapon) for better – and for worse.

For better, in the sense that businesses are able to make plans, investment and hiring decisions that had been paused may now be resumed.

Most exporters know what size tariffs their goods face – and can figure out how to accommodate or pass on the cost to consumers.

That growing sense of certainty underpins a more relaxed mood in financial markets, with shares in the US notably gaining.

REUTERS/Evelyn Hockstein

REUTERS/Evelyn HocksteinBut it’s for the worse, in the sense that the typical tariff for selling into the US is higher than before – and more extreme than analysts predicted just six months ago.

Trump may have hailed the size of the agreement of the US with the EU – but these are not the tariff-busting deals we equated with tearing down trade barriers in previous decades.

The greatest fears, the warnings of potential disaster, have receded. But Ben May, Director of global macro forecasting at Oxford Economics, says that US tariffs had the capacity to “damage” the global economy in several ways.

“They are obviously raising prices in the US and squeezing household incomes,” he says, adding that the policies would also reduce demand around the world if the world’s largest economy ends up importing fewer goods.

Winners and losers: Germany, India and China

It’s not just about the size of tariff, but the scale of trading relationship with the US. So while India potentially faces tariffs of over 25% on its exports to the US, economists at Capital Economics reckon that, with US demand accounting for just 2% of that nation’s gross domestic product, the immediate impact on growth could be minor.

The news is not so good for Germany, though, where the 15% tariffs could knock more than half a percentage point off growth this year, compared to what was expected earlier in the year.

That’s due to the size of its automotive sector – unhelpful for an economy that may be teetering on the brink of recession.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesMeanwhile, India became the top source of smartphones sold in the US in the last few months, after fears of what may lie in store for China prompted Apple to shift production.

On the other hand, India will be mindful that the likes of Vietnam and the Philippines – which face lower tariffs when selling to the US – may become relatively more attractive suppliers in other industries.

Across the board, however, there’s relief that the blow, at least, is likely to be less extensive than might have been. But what has been decided already points to longer-term ramifications for global trading patterns and alliances elsewhere.

And the element of jeopardy introduced into a long-established major relationship with the US, lent added momentum to the UK’s pursuit of closer ties with the EU – and getting a trade deal with India over the line.

For many countries, this has served as a wake up call – a need to remain alive to fresh alliances.

A very real political threat for Trump?

As details are nailed down, the implications for the US economy become clearer too.

Growth in the late spring there actually benefitted from a flurry of export sales, as businesses rushed to beat any higher tariffs imposed on American goods.

Economists expect that growth to lose momentum over the rest of the year.

Tariffs that have increased from an average of 2% at the beginning of the year to around 17% now have had a notable impact on US government revenue – one of the stated goals of Trump’s trade policy. Import duties have brought in more than $100bn so far this year – about 5% of US federal revenue, compared to around 2% in past years.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said he expected tariff revenue this year to total about $300bn. By comparison, federal income taxes bring in around $2.5tn a year.

American shoppers remain in the front line, and have yet to see higher prices passed on in full. But as consumer goods giants such as Unilever and Adidas start to put numbers on the cost increases involved, some sticker shock, price rises, loom – potentially enough to delay Trump’s desired rate cut – and possibly a dent to consumer spending.

REUTERS/Evelyn Hockstein

REUTERS/Evelyn HocksteinForecasts are always uncertain, of course, but this represents a very real political threat for a president who promised to lower consumer prices, not take actions that would raise them.

Trump and other White House officials have floated the idea of providing rebate checks to lower-income Americans – the kinds of blue-collar voters who have fuelled the president’s political success – that would offset some of the pocketbook pain.

Such an effort could be unwieldy, and it would require congressional approval.

It’s also a tacit acknowledgment that simply boasting of new federal revenue to offset current spending and tax cuts, and holding out the prospect of future domestic job and wealth creation is politically perilous for a Republican party that will have to face voters in next year’s midterm state and congressional midterm elections.

The deals yet to be hammered out

Complicating all this is the fact that there are many places where a deal is yet to be hammered out – most notably Canada and Taiwan.

The US administration has yet to pronounce its decisions for the pharmaceuticals and steel industry. The colossal issue of China, subject to a different deadline, remains unresolved.

Trump agreed to a negotiating extension with Mexico, another major US trading partner, on Thursday morning.

Many of the deals that have been struck have been verbal, as yet unsigned. Moreover it is uncertain if and how the strings attached to Trump’s agreements – more money to be spent purchasing American energy or invested in America – will actually be delivered on.

In some cases, foreign leaders have denied the existence of provisions touted by the president.

YURI GRIPAS/POOL/EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

YURI GRIPAS/POOL/EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockWhen it comes to assessing tariff agreements between the White House and various countries, says Mr May, the “devil is in the detail” – and the details are light.

It’s clear, however, that the world has shifted back from the brink of a ruinous trade war. Now, as nations grapple with a new set of trade barriers, Trump aims to call the shots.

But history tells us that his overarching aim – to return production and jobs to America – may meet with very limited success. And America’s long-time trading partners, like Canada and the EU, could start looking to form economic and political connections that bypass what they no longer view as a reliable economic ally.

Trump may be benefitting from the leverage afforded by America’s unique position at the centre of a global trading order that it spent more than half a century establishing. If the current tariffs trigger a foundational realignment, however, the results may not ultimately break in favour of the US.

Those questions will be answered over years, not weeks or months. In the meantime, Trump’s own voters may still have to pick up the tab – through higher prices, less choice and slower growth.

Additional reporting: Michael Race. Top image credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.